Words long forgotten and never known — On rare terms of book printing and printmaking

BY | RU | EN

DOI: http://doi.org/10.54544/662

|

In the July 2020 issue of Science and Life, a popular Russian-language science monthly published in Moscow, an article appeared which was devoted entirely to the leather ink balls. It turned out that not only the tool itself is no longer in use, both the word and the concept have all but disappeared. This web publication provides an abstract of the Science and Life paper, and makes use of the materials covering the similar printing tools which were excluded from the paper due to space limitations. |

||

|

Briefly about ink balls

The tool turned out to be an ideal solution for a specific technical problem — to spread the printer's ink into a uniform thin layer and to apply it to the raised elements of a letterpress form or a woodcut block. The ink balls entered the public consciousness, became an ubiquitous attribute of typographic signs, printer's devices, professional guild and personal heraldic emblems, and even playing cards. |

|

|

|

And then the 19th century brought about the industrialization. In England, a new material, a predecessor of rubber, was invented. It became known as a composition — a mixture of molasses, tar and glue. When solidified, this material forms a hard but elastic substance (which became known as масса in Russian). At first, the composition just replaced the wool-stuffed leather pad, so that the ink balls retained their traditional shape. But very soon people figured out how to shape the composition into a solid seamless cylinder. Thus a composition roller was born. The era of the leather ink balls came to an end.

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

After the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, the Soviet authorities did their best to completely write off the ink balls in an attempt to "renounce the old world" (quoting the opening line of the Russian Communist adaptation of La Marseillaise, the French national anthem with the original lyrics by Claude Rouget de L'Isle). Thus, the word is absent from the key explanatory dictionaries of that period, as well as from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Forgetting something does not require much sophistication. Starting form about mid-60s, some scientific papers on history of technology contained a discovery: "To ink the movable type, a printer would use a маца, that is, a large leather glove." However, this is not the limit for a confusion. Today, in multiple traditional and online publications (appearing under different names, so crediting the original author may not be easy), the instructions how to prepare the ink balls for a work shift appear to have been copied verbatim — from the kosher culinary books giving delicious recipes of dishes with matzot! |

||

|

Nevertheless, through the efforts of living history museums and early printing enthusiasts around the world, the ink balls — this culturally important object — survive even today. One can see them in operation or even try oneself in the art of printing working as a beater (aka батырщик or battitore). On the illustration to the right, Gary Gregory, the founder, president, and director of The Printing Office of Edes & Gill in Boston, MA, demonstrates the operation of a press during the period of American Revolution. Whereas this video link would bring the reader to the printing demo at the Crandall Historic Printing Museum in Alpine, UT, founded by Louis E. Crandall in 1988. |

|

|

|

The Italian word mazza (a bat) is functional. In many other languages, as in English, the corresponding term points to the round shape of the implement: German — Druckerballen, English — ink ball, Dutch — inktbal or drukkersbal, Finnish — väripallo, French — just balle.

|

|

|

|

We shall now focus on the other applications of relief printing and the tools that are used in such applications. Printing on fabric |

||

|

Printing on fabric is ubiquitous in many cultures around the world and can trace its roots to by far more ancient times than book printing. A printing block with raised pattern is covered with ink or dye (to apply to the fabric in the direct printing method), etchant (to remove color from the already uniformly dyed fabric), or resist (such as wax, to prevent color transfer to the specific areas in the course of subsequent dyeing). Then the pattern is transferred from the printing block to the fabric, and fabric is subjected to any post-processing, if necessary. The most ancient examples of printed fabrics within the realm of the former Russian Empire are dated back to approximately 11th century. Those had been discovered in 1874 by a prominent Ancient Rus archeologist D.Ya. Samokavsov (1843–1911) during the excavation of the burial mounds near the village of Lenivki in the Chernihiv province in Ukraine.

|

|

|

|

The second of the methods described in the literature is used largely in Ukraine. A printing block (Ukr. лице́ [litse]) is mounted horizontally with the carved surface facing up. The fabric then is placed on top and either tapped or rolled in from above. To task of applying ink or paint to the surface of the block is solved with a pair of leather pads known in Ukrainian as товку́ши [tovkushi]. "Tovkusha, -shi, fem. — among fabric printers, a tool for applying the paint to the pattern block: a square board with a handle on top and a leather pad below." (Словарь української мови: в 4-х тт. / За ред. Б. Грінченка. К., 1907–1909. V. 4. P. 270.) There is a direct analogy between tovkushi and typographic ink balls. "The paint is applied to the two stuffed leather pads (or tovkushi). These pads are attached to the rectangular boards with handles. First, they are beaten against each other to spread the paint uniformly, and then beaten against the carved pattern board to cover it with paint." (Н. Дубина «Откуда есть пошла»... печать по ткани.) An example of the pattern block for fabric printing with the miniature design elements is shown in the illustration on the right. Its design suggests that, most likely, the paint is supposed to be applied to it with an ink pad (tovkusha) rather than by pressing against a paint-saturated cloth. The block is made by wood carving and embellished with multiple copper inserts — in the form of plates and wires, — that allow creating of fine and sharp pattern lines. Stone rubbing (China) |

|

|

|

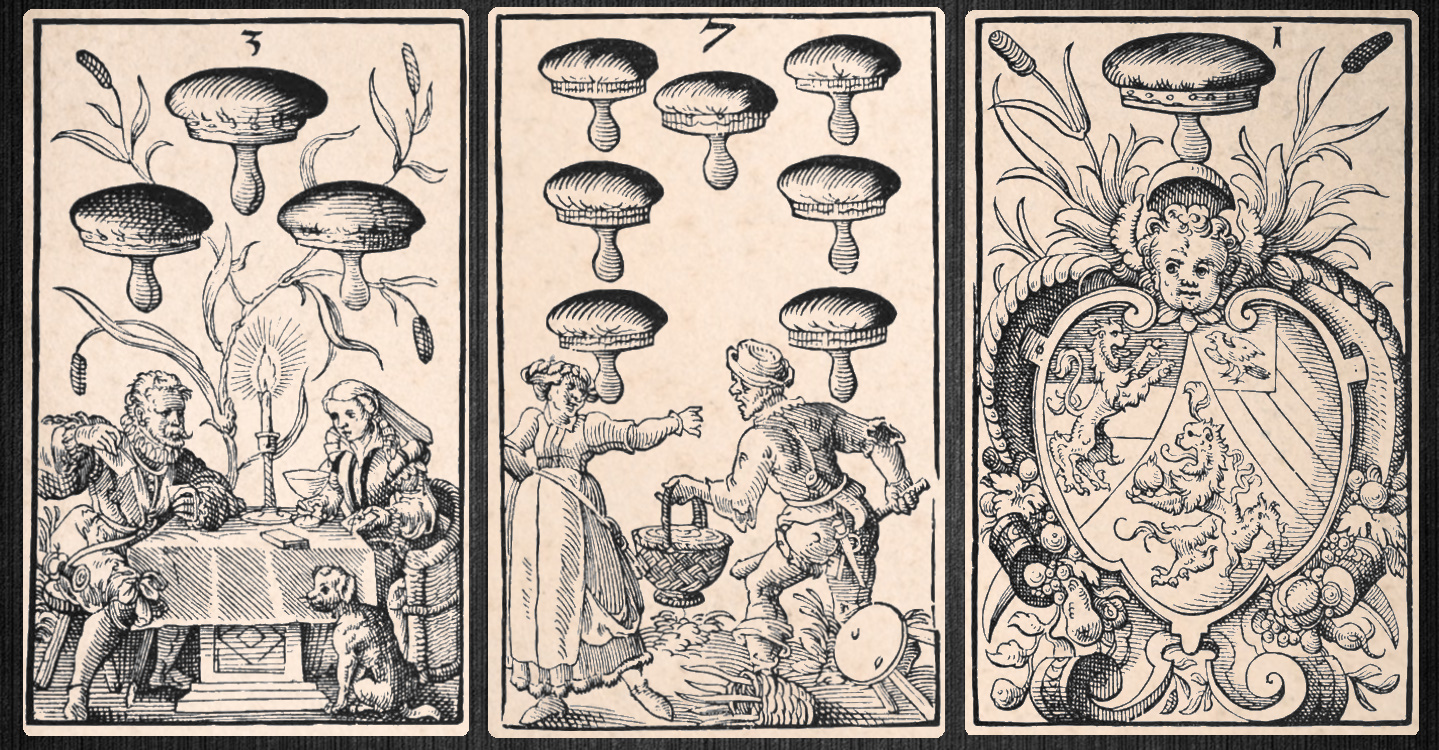

Since the ancient times, it has been a tradition in China to immortalize in stone the most important canonical texts: Analects by Confucius, works of classical poetry, Buddhist sutras, calligraphic masterpieces, and so on. Stone, or stele, relief cutting has become a special plastic (i.e., three-dimensional) art form. With invention of paper in the second century C.E., it became possible to create copies of such reliefs for public and private libraries, which led to the birth and development of a new kind of graphic art. This graphic art form is nowadays denoted with the character 拓 (tà or tuò) and is known in English as stone rubbing. It is believed that its history goes back at least one and a half thousand years. |

|

|

|

Making a rubbing imprint on paper involves the use of an instrument known as 拓包 (tà bāo) which looks very much like a typographic ink ball. The second character means a packet, a wrap, or a dumpling. The name of this tool is commonly translated into Russian as тампон табао, or, literally, a tabao pad. A moistened sheet of paper is laid over the inscribed stone surface; then a special brush is applied to tamp the paper into every depression on the surface. Thereafter the artist uses one or two tabao pads (on a vertical or horizontal surfaces, respectively) to apply the coloring pigment to the exterior side of the paper sheet. In doing so, the depressed areas remain uncolored. As a result, an imprint of the inscribed surface is formed on the paper, which, unlike the letterpress or engraving print, is a direct copy of the original form, rather than its mirror image. |

|

|

|

For many centuries of its history, the art of stone rubbing has developed numerous styles and directions. The most obvious classification criterion is based on the type of coloring pigment: the 墨拓 (mò tà) type imprints employ back ink, whereas the 朱拓 (zhū tà) type imprints, the cinnabar or other bright red pigment. Also, already more than a thousand years ago, the distinction emerged between the imprints of "golden-black" style made in the saturated shiny black tone (烏金拓, wūjīn tà), and the imprints of the "cicada wing" style with light translucent shades, which form what can be called a graphic rhyme (蝉翼拓, chányì tà). A more detailed description of the stone rubbing can be found in the Russian-language paper by V.G. Belozerova. In addition, a small-form demonstration at the Taiwan Historical Museum in Nantou City (Taiwan) covers all stages of making a rubbing imprint in a short time.

|

|

|

|

Polychrome xylography (Japan)

|

|

| < Папярэдні | Наступны > |

|---|