The rivers of Muscovy in the travelogue of Ambrogio Contarini

BY |

RU | EN

DOI: http://doi.org/10.54544/687

|

The Venetian diplomat Ambrogio Contarini (1429-1499), a member of one of the oldest and noblest Venetian family clans which gave the Serenissima Repubblica no less than eight doges, became the first foreign traveler who, in a printed book, brought an eyewitness testimony about the Moscow state to the Western Europeans. His visit to Muscovy occurred at the final stage of a three-year-long diplomatic mission (1474-1477) with the main goal of conducting the alliance negotiations with the Persian ruler Uzun Hasan. Here we will focus on the cartographic, rather than political, implications of his journey. A river called Monster As Contarini reports in his travelogue, on August 10, 1476, he departed from Astrakhan (Citrachan) with a merchant caravan heading for Moscow. For the first 15 days, the caravan traveled along the left bank of the Volga river, then crossed it on the rafts and continued its way across the steppe. Finally, on September 22, the caravan reached the lands of Ruscia, and on September 25, having passed the cities of Ryazan (Resan) and Kolomna (Colona) on the way, Contarini arrived to the city of Moscow (la terra di Moscouia), “belonging to the Grand Duke Zuanne, to the sovereign of White Ruscia". He stayed there until January 21, 1477, and then, after receiving the permission from the Grand Duke, left the Moscow realm and departed on a sleigh from Moscow via Vyazma (Viesemo) and Smolensk (Smolenzecho) in the direction of the Trakai Castle (Trochi) in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania [1, C20–C36]. The route of this journey along with all its twists and turns is well known from the travelogue compiled by Ambrogio Contarini himself. Besides, those who have studied it carefully enough could be aware of an obscure passage concerning the description of a river near Kolomna. The city of Kolomna, which the caravan reached on September 23 or 24, is situated, according to Contarini, next to a river, and "there is a large bridge over which this river is crossed, and it flows into Volga" [1, C27]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is well-known that Kolomna is located at the confluence of two rivers: the mainstream Oka, and its left tributary river Moskva (or Moscow river). Some 600 km downstream Oka in its turn falls into the river Volga. Had Contarini limited his description of the river to the above quote, no one would have doubts — he meant Oka. Indeed, a glimpse on the map is sufficient to convince oneself: if you travel along the right bank of the Volga river towards the city of Moscow, it is Oka which lies on your way as a water barrier. Out of the two cities passed by the caravan and mentioned in the travelogue, Ryazan is located on Oka's southern bank, and Kolomna, on the northern bank. It is necessary to cross Oka in order to advance further north-west going upstream along its left tributary, the Moscow river (it does not matter which bank) to reach the capital of the Moscow state. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

However, Contarini didn't limit his description of the river to the information about the bridge and confluence with Volga. He also reported the name of the river, and that was what stirred confusion among many generations of editors, translators, and readers. One can find different names in the different editions of the travelogue. In the traditional 1836 Russian translation by V.N. Semyonov [2] (as well as in the popular English translation by William Thomas issued by the Hakluyt Society [3]) the river is called Moscow (Mosco). In the modern 1971 translation made under the auspices of the Soviet Academy of Sciences and edited by E.Ch. Skrzhinskaya [1] the river is given a somewhat mysterious name Mostro, which translates into "monster", as the attached illustration graphically demonstrates. The subsequent historical publications, in particular, the 2001 paper by O.F. Kudryavtsev [4], use the same word. The authors are convinced that Mostro denotes the Oka river, but neither makes an attempt to explain such a peculiar name. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The divergent river names in the two Russian translations can be easily explained by their different sources. The 1971 academic translation was made after the original text of the 1543 edition in the Veneto language where the river was called Mostro. (The Veneto language is a Romance language, viewed sometimes as an Italian dialect, which is spoken in the city and region of Venice as well as in some areas of the Mediterranean that used to be associated with Venice). However, in the 19th century the original text was not as readily available as its Italian translation that Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485–1557) had included into the second volume of his collection of voyages titled "Navigationi et viaggi". This volume was published in 1559, already after the death of the compiler. Apparently, trying to make sense out of the vague river name, its editors thought it to be a typo and used the word Mosco instead — to match the name which Contarini called the river flowing within the city of Moscow. As a result, the river near Kolomna is called Mosco in all numerous Ramusio reprints, including that of 1606 which formed the basis for the Russian translation by V.N. Semenov. However, the question remains where Contarini obtained the name Mostro, and if the author of the travelogue made a mistake, what the matter of his confusion was. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

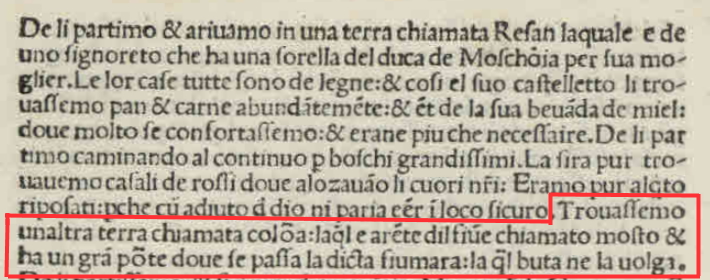

The confusion of Ambrogio Contarini In order to find the answer, we turn to the very first edition of Contarini's travelogue and the only one made in the author's lifetime, which was published in Venice in 1487. Here a great surprise is awaiting us! The name Contarini himself gave to the river was Mosto. We reproduce the fragment of interest in a form which is more familiar to today's reader, expanding ligatures and diacritical abbreviations, and provide its English translation. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Trouassemo unaltra terra chiamata colona, laqual e arente dil fiume chiamato mosto et ha un gran ponte doue se passa la dicta fiumara, la qual buta ne la uolga. We arrived at another city called Colona, which is situated near a river called Mosto and has a large bridge to cross said river, which flows into Volga. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The text leaves no doubt whatsoever. The Russian word for bridge is мост which is transliterated and pronounced as most. The author of the travelogue mistook the common Russian word denoting a hydraulic structure for the name of the river. Noteworthy, this word appears in the 1487 edition only. Having checked the other known early editions of the travelogue, we don't find the word Mosto in any of them. For reader's convenience, the following table summarizes the results of the search; each edition carries a hyperlink to the actual text.

Thus, the subsequent publishers and translators, likely striving to maintain coherency of the text, tried to find a meaningful replacement for the incomprehensible word Mosto, which led them to the Mostro and Mosco variants. Note that one should not expect any deep significance in the lowercase and uppercase spelling of the word Mostro. In all those editions where the word mostro is typeset with a lowercase letter, the name of another river, uolga, is set in lowercase as well, and vice versa. What we are dealing here is not a semantic difference, but the difference in traditions or personal preferences of the typesetter. We have seen now that the mysterious river name in Contarini's travelogue was concealing neither the Moscow river, nor an ominous monster, but was a confused representation of a familiar Russian word for bridge. This fact had been lying on the surface, hidden in the plain view. To discover it, one had just to check the obscure text fragment against the first edition of the travelogue. According to E.Ch. Skrzhynskaya ([1], p.90), a copy of this edition is found in Saltykov-Schedrin Russian national library in St. Petersburg (holding number 9.XIII.3.29). Furthermore, she used that edition to verify some of the toponyms (see [1], comm. 133, 134 on p. 247). However, the river Mostro apparently has escaped that fate both in the preparation of the 1971 academic translation, and in the aftermath. The latter fact is evidenced not only by the silence of the Russian publications on the subject matter, but also by a correspondence dialogue in which the author of this article took part as recently as in August 2021. As an interlocutor, I was facing a prominent historian, a medieval source expert, a senior researcher at one of Moscow's academic institutions and an author of publications concerning Ambrogio Contarini and Paolo Giovio. In other words, there were sufficient objective reasons to expect that his knowledge on the subject of our conversation would reflect the most advanced level of Russian historical thought. However, his response to my observation about the word Mosto in the first edition of Contarini's travelogue was that of condescending mentoring skepticism. He questioned not only my interpretation of the text, but the mere fact that I quoted the 1487 edition: Dear Denis, This comment provides ample confirmation that not only the professional Moscow historian and expert had been unaware of the original river name used by Contarini in his travelogue, but also the first 1487 edition as a whole had remained beyond his horizon. This comment, therefore, assures the novelty of the findings presented here. The graphic quote, which I sent in response and which left no room for any kind of paleographic doubt, elicited an emotional reaction: Wait! What the hell! Do you have Contarini's first edition of 1487!? Where on earth did you get it from!? I have and use only the second one — "Itinerario del magnifico e clarissimo messer Ambrosio Contarini… ", year 1524! Let's now focus on one of the two later interpretations, specifically, that the river that crossed the path of the caravan near Kolomna and that was flowing into Volga was indeed the Moscow river. By just looking at the table of the early printed editions, one may arrive at the conclusion that such an interpretation was formed in 1550-s thanks to the editors of Ramusio's "Navigationi et viaggi" collection of travels (the second volume of which was printed in 1559, but could have appeared earlier being delayed by a fire that ravaged the publishing house). Herein we advance an alternative proposition: this interpretation was formed a few decades earlier — in the first quarter of the 16h century or even in the 15th century. This proposition has a clear visual proof, one convincing evidence, and one indirect confirmation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

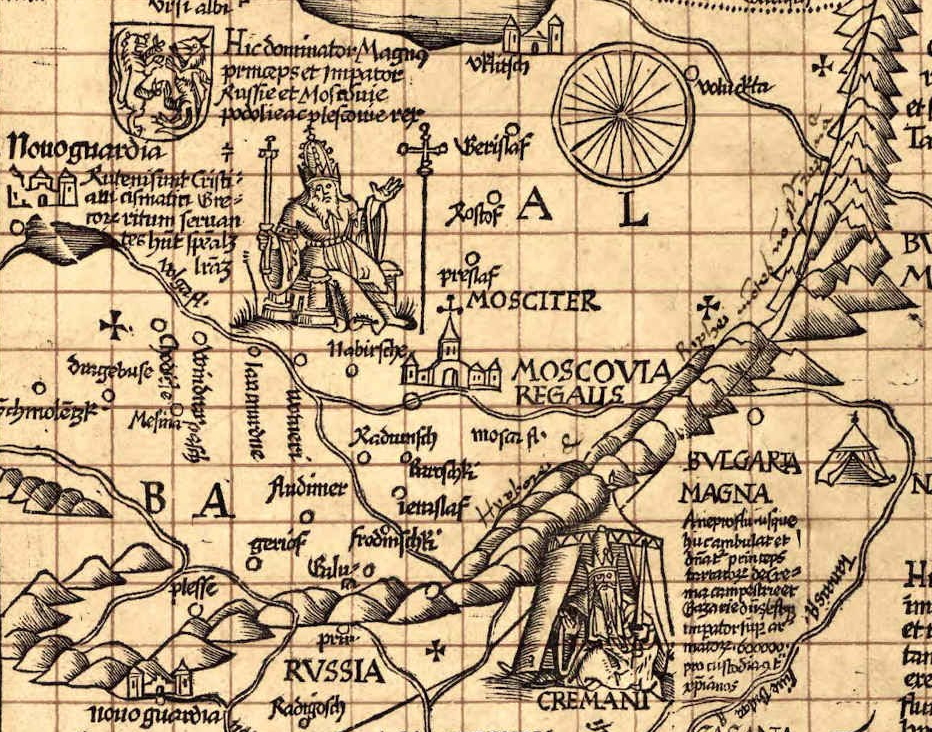

The confusion of the interpretations As a clear visual proof, let's consider the manuscript map entitled Tab[ula] Mod[erna] Tartarie, or "Modern map of Tartary". By Tabulae Modernae, or Tabulae Novae, the 16th century mapmakers meant the maps that were used to complement the classic set of 26 or 27 Ptolemaic maps comprising many editions of "Geographia" by Claudius Ptolemy, a 2nd century Greek cartographer. The Tabula Moderna Tartarie first surfaced in 1970-s in a private collection. In 2009 it was sold in the Sotheby's auction. Later in 2011 it was acquired by the Dutch antiquarian bookseller and researcher Frederik Muller, thanks to whom it became known to the cartographic historians. The research papers about this map were published by the well-known German historian Peter Meurer (1951–2020) [5] and Frederik Muller himself [6]. In 2018, the map was sold once again, and is presently in private hands (Frederik Muller, private correspondence, Sept 2021).

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

From the perspective of its cartographic content, the manuscript map of Tartary represents an attempt to combine the classical Ptolemaic concepts (in particular, those involving the Riphean and Hyperborean mountains where all the rivers originate) with the recently reported geographical data. Among the latter, as the text on verso clearly indicates, was the information about Muscovy provided by Ambrogio Contarini. The map indeed shows the key points of his itinerary: the cities of Citracam, Resan, Colona, Moschouia, Viesemo, Smolenzech, as well as the fictitious city of Nagai, apparently symbolizing the Tartar nomadic camps between the rivers of Volga and Tanais (Don). These points perfectly fit onto a large and smooth arch marking Contarini's route. Then, while continuing to study the map, we come across an incredible feature: the Moscow river (Moscus f.) is shown to fall into the sea of Azov (Palus Meotis)! How could such an absurdity come to someone's mind!? But let's not rush to ridicule the ignorance of the mapmaker. The Tabula Moderna Tartarie opens for us a rare and unique opportunity to embark on time travel and, going half a millenium back, visit the study of the 16th century cartographer. Over there we will be surprised to find out that all his decisions are logical and thoroughly motivated. On the desk in front of him, the cartographer has all sources that he needs to tie into a unified and consistent graphical representation. First of all, that includes the unquestionable inheritance of antiquity blessed by the generations of his predecessors: the Ptolemaic Eighth map of Europe and Second map of Asia. Secondly, that includes one or both editions of Contarini's travelogue (1524 and, possibly, also 1487), which have been published so far. Finally, that includes a diverse collection of oral and written information gems of various origin. As the basis for his map, he takes the Second map of Asia, expanding its coverage to the north and to the east. We cannot avoid mentioning that, in comparison to Ptolemy, Lorenz Fries shifts all the geographical features by 2 degrees to the north. For example, according to Ptolemy, the source of Tanais is located at the latitude of 58°N; however, Fries shows it at 60°N. We should not overvalue the significance of that shift; it is systematic in nature and, apparently, results from a random error of the kind which is not uncommon to the 1525 Strasbourg edition (take a notice of unmatching latitude scales of the two Ptolemaic maps mentioned above). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Further, the cartographer must rationalize, in the light of the Ptolemaic concepts, the surprising fact that Contarini traveled his entire route through Muscovy across the plains, without encountering any mountains on the way. Here Fries is forced to compromise by introducing an amendment to the classical Ptolemaic heritage. In the Riphean mountain range, he depicts a gap through which one can get across the plain from Moscow to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and through which a river flows from west to east, connecting Vyazma, Moscow and Kolomna. Nevertheless, he puts the source of this river on the western slope of the Riphean mountains — in full accordance with the principles of Ptolemy! Finally, the compiler of the map has to deal with the river and the bridge near Kolomna. He is justly suspicious of both the name Mosto in the 1487 edition, and to the name Mostro in the 1524 edition. These are more than strange names that none of the knowledgeable people mention. Could there be an error made by a typesetter or a proofreader? The solution is suggested by the author of the travelogue himself — of course, this is the river Mosco, the same one that flows through the state capital. And Lorenz Fries depicts the city of Kolomna at the confluence of two rivers, one of which — Moscus f. — must be crossed to get to the city of Moscow. What remains is Contarini's assertion that the river flows into Volga. But now the river Moscus is reliably separated from the Volga by the Don! Connecting the Moscus with the Volga is impossible in principle, and the cartographer has no choice but to dismiss this assertion as a mistake and to direct the river Moscus in the most logical direction — southwards into the Sea of Azov. The desperation of this gesture, along with the scrupulousness that the mapmaker had a chance to demonstrate with respect to his sources, convince us that, although he did not find a satisfactory solution, the problem of finding a graphical interpretation to the statement "the Moscow river flows into the Volga" was indeed formulated by him! Two additional examples provide evidence that in the first quarter of the 16th century this idea was already in the air. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

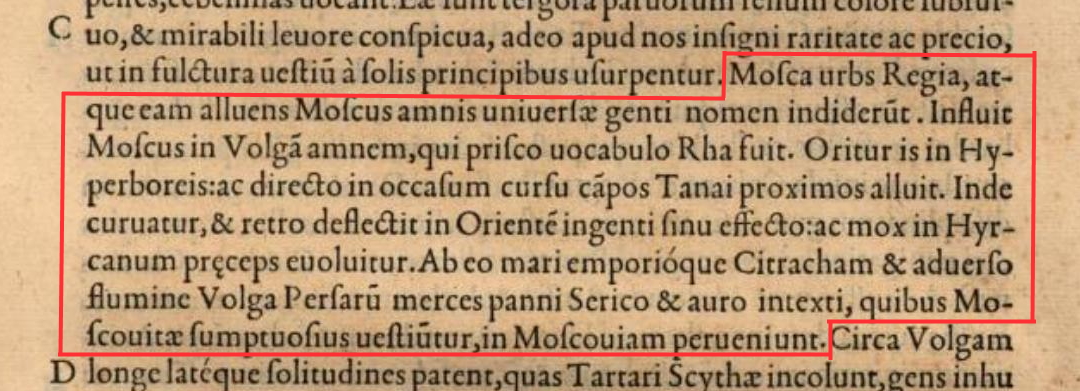

For the second example, the author of the present article is thankful to his respected academic mentor, who has called his attention to the celebarted Historiarum sui temporis ("History of my time"), a historical treatise in 45 books on which the Italian humanist physician, historian and prelate Paolo Giovio (1483–1552) had been working for a large portion of his life. The book which the author completed first in 1515 and which at the time of publication was designated XIII, Giovio makes an unequivocal statement that river Moscow is a tributary of Volga. Here we attach a graphic quote and provide both the modern transcription and the English translation: Mosca urbs Regia, atque eam alluens Moscus amnis universae genti nomen indiderunt. Influit Moscus in Volgam amnem, qui prisco vocabulo Rha fuit. Oritur is in Hyperboreis; ac directo in occasum cursu campos Tanai proximos alluit. Inde curvatur, et retro deflectit in Orientem ingenti sinu effecto; ac mox in Hyrcanum praeceps evolvitur. Ab eo mari emporioque Citracham et adverso flumine Volga Persarum merces panni Serico et auro intexti, quibus Moscovitae sumptuosius vestiuntur, in Moscoviam perveniunt. The capital city Mosca and the river Moscus flowing through it gave the name to the whole nation. The Moscus flows into the Volga river, which in ancient times was called Rha. It originates in the Hyperborean mountains and, taking the course directly to the west, flows through the plains closest to Tanais. Then it curves and deflects back to the east, making an enormous loop, and soon rapidly discharges into the Hyrcanian sea. From that sea, via the city of Citrachan and up the flow of Volga, the Persian goods arrive in Muscovy, such as gold-embroidered silk fabrics that the Muscovites wear sumptuously. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The author of this article asserts that the use of the name Citrachan reliably confirms that Paolo Giovio wrote these words under the influence (perhaps, indirect) of Contarini's report. It is precisely the name under which the city of Astrakhan appears in the first (1487) and all subsequent editions of the travelogue. On the other hand, the name does not appear in the other printed and manuscript sources which predate its borrowing by Giovio. The latter conclusion was made by Peter Meurer and Frederik Muller who specifically researched this issue (Frederik Muller, private correspondence, Sept. 2021). Speaking of another potential source from which Giovio could have obtained the name of the city, the 14–15th century portolan charts, a reference provided by Ramon Josep Pujades, the top expert in this branch of the history of cartography, confirms that the name Citrachan or the similar ones do not appear in portolan charts. Among the Russian researchers, I.V. Zaitsev attributes the name Citrachan to the "Battista Agnese map" [7, p.231], that is, effectively, to Paolo Giovio and his map of Muscovy of 1525. A reservation is due at this point: the 13th book of the treatise remained in manuscript form for 35 years and was published only in 1550. Could have the author made a revision of the manuscript at a later time, or could have publishers and editors introduced some corrections at the time of publication, not unlike Giovanni Ramusio did in 1559, when he, for sake of uniformity, unceremoniously corrected to Citrachan the original names Githercan and Ghetercan which another Venetian diplomat and traveler Josafat Barbaro used in his work? To answer this question and to address the reservation, let's first point out the evidence against revisions made by the author. The Moscus river flowing into the Volga and the city of Citrachan are mentioned within the same paragraph. Had Paolo Giovio, who already in 1525 received information about the Oka River from conversations in Rome with Dm. Gerasimov, undertaken to make a minor correction to the name of the city, he would have certainly corrected an actual inaccuracy in the text. The editorial change is highly unlikely. Firstly, the name Citrachan occurs only once in the treatise and, therefore, there is no question of uniformity, Secondly, Giovio is not an author whose words can be unceremoniously edited. In addition, the content of the fragment, that is, the description of the trade in Persian fabrics along the Volga with Moscow, is practically a transposition of Contarini's notes (cf. [1], C17, C20). Thus, we consider that example to be a convincing piece of evidence in favor of the above proposition. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The present article justifies (to the best of its author knowledge, for the first time) the following conclusions:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Afterword: An encounter with a learned professional The reader has probably noticed that, contrary to the common research etiquette, in this article I don't provide the name of my respected academic mentor, to whom I am grateful for the discussion that has taken place between us and for a recommendation concerning the treatise by Paolo Giovio. Explaining the reasons of doing so in this Afterword, I would refer to him by the appropriate initials: K.P.T. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The author of this article is not a professional historian, but an engineer. The old maps and the history of cartography is my hobby for which I can spare just rare leisure minutes, as I devote the lion share of time to my engineering business. At the same time, the observations and ideas that formed the basis of this article are quite simple — so simple that some professional historian can be deeply annoyed: "How come the idea has lying on the surface in everyone's plain view, but it was not me who found it, but some undeserving amateur techie!" This feeling is not difficult to explain or sympathize with. I would have been annoyed too, if a historian or a geographer took from under my nose — well, let's say, the idea of contention-based grants in the passive optical networks...

When the conversation switched to Ambrogio Contarini and his travel to Muscovy, I made a reference (see the main part of this article above) to the first 1487 edition of his travelogue, eliciting a strong reaction from my dialogue partner, who, as it turned out, didn't have this edition at his disposal and was not familiar with its peculiarities. In effect, an amateur hurt the self-esteem of a professional historian and medieval primary source expert. In an attempt to defuse the situation, I tried to reach out for the virtual handshake and sent him a copy of Peter Meurer's paper on the 1524 manuscript map of Tartary, sharing some of my findings about it. But that might just have made the things worse... A few days later, I received a letter with an attached paper draft. In the letter, he wrote that, since his employer forced him to publish, he couldn't resist temptation and "concocted" a paper for "an insignificant ugly journal" and was asking my opinion about it. The letter also contained his last compliment, which was hardly the most elegant, but certainly the most memorable: I look at you with amazement. How did you manage to get so loaded, having a completely different profession ?! I do not understand. The paper draft was sad. A part of it addressed the topic of our conversation, but my name was mentioned once in the context of an insignificant triviality, whereas the observations of the imago.by publication and all the findings I discussed with him over email were presented as if his own. The "River called Mosto" story was appropriated too. Still believing it could have been just a poor choice of syntax, I wrote back pointing out the ambiguities in attributions of the ideas and asked to avoid those ambiguities in the published paper. At that point our three-week-long conversation came to an abrupt end. In a message which arrived the next morning, my dialogue partner announced that his desire to collaborate or maintain correspondence with me was no longer. He also provided an admonition and an advice: First, write about your scrawny "discoveries" yourself! The expression "to serve science" and the words "to share" and "obligation" puzzled me, at first. "Didn't I share with you the 1487 edition of Contarini and the paper by Peter Meurer?" I thought. But then I came across a consistent explanation. If my academic mentor considers himself a personification of history, it is not totally surprising that anyone who starts a conversation with him becomes in his eyes a personal servant of his. Then "sharing" for him is not limited to the sources, but easily encompasses the other people's results which he would be eager to claim as his own. Not at all unlike a medieval relationship between a lord and a vassal, or more up-to-date relationship between Don Vito Corleone and his "family". The advice I received was even more instructive. By making use of the exquisite word "scrawny", my highly respected academic mentor, at his own will and choosing, put himself on par with those trained professionals who, when caught red-handed, would invariably yell, "Take back your scrawny nag! Why the hell would I need it?" On the other hand, I am indeed used to taking the results of my historical investigations with a grain of irony, but does not the inescapable desire of a professional historian and primary source expert to make me "share" my findings with him provide evidence that I have been underestimating them? Thus, I found sense in K.P.T.'s words. So I decided to use the piece of good advice and to write about my findings myself. The result was this article. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| < Папярэдні | Наступны > |

|---|

![Lorenz Fries, 1524. Tab[ula] Mod[erna] Tartarie. Manuscript. Ink on paper. 40.5 х 54 cm. Watermark: a glove with a cuff and a flower over the middle finger](/images/stories/Articles/20/mostro/rimu_a_1382099_f0002_b.jpg)

![Lorenz Fries, 1524. Tab[ula] Mod[erna] Tartarie. Manuscript. Text on verso.](/images/stories/Articles/20/mostro/rimu_a_1382099_f0005_b.jpg)

![Lorenz Fries, 1524. Tab[ula] Mod[erna] Tartarie. Fragment.](/images/stories/Articles/20/mostro/fries-1524-fragment-v1.jpg)