Падобныя матэрыялы

- Ян Блаў. Карта ВКЛ 1635 год. MAGNI DVCATVS LITHVANIAE

- Рэнье і Жошуа Отэнсы 1726 год. MAGNI DUCATUS LITHUANIAE

- Юстус Данкертс 1695 год. MAGNI DUCATUS LITHUANIAE

- Матэўс Зойтэр 1735 год. Novissima et accuratissima MAGNI DUCATUS LITHUANIAE

- Калекцыя. Старадаўнія карты, гравюры

- 400 год Радзівілаўскай карце

- Выстава "Беларусь на старинных географических картах"

- Беларусь на Эбсторфскай карце ХІІІ ст.

- Азартная геаграфія Вялікага Княства Літоўскага

- Игральные карты и география

- Марсэль ван дэн Брок. Даведнік па атласных картах Абрахама Артэліўса

- Станіслаў Александровіч - штурман картаграфіі ВКЛ

- Точная датировка антикварных карт Абрахама Ортелиуса

- Альбом "Брэст на старадаўніх картах і планах" да 1000-годдзя Берасця

- Александр Корнилов - реконструктор старинной графики

- Аляксандр Карнілаў - рэканструктар старадаўняй графікі

- Аб удакладненні датавання карты ВКЛ ўзору 1613 года

- Об уточнении датировки карты Великого Княжества Литовского образца 1613 года

- Наватарская карта Сарматыі Бярнарда Вапоўскага

- Маторы БНР. Праект стварэння беларускай авіяцыі [дакумент]

- Знойдзены другі асобнік чарцяжа Масковіі Паўла Джовіа 1525 года

- Рукапісная карта Літвы і Польшчы 1600 года з калекцыі ARSI

- Рукописная карта Литвы и Польши 1600 г. из собрания ARSI

- Выйшла кніга Станіслава Александровіча "Картаграфія Вялікага Княства Літоўскага"

- Альбом "Мінск на старадаўніх картах і планах"

- Агляд выдання Тэцяны Люты "IMAGO URBIS: Киів на стародвиніх мапах"

- Уладзімір Шчасны — надзвычайны і паўнамоцны пасол ад культуры

- Выданне “Ян Няпрэцкі і карта ВКЛ” А.Адамовіча ў кантэксце гісторыі картаграфіі

- Картаграфічны вобраз беларускай сталіцы

- Ян Няпрэцкі і яго карта ВКЛ

The Innovative Map of Sarmatia by Bernard Wapowski, 1526

BY | EN

This article presents the continuation of research of the map of Sarmatia, created by a prominent Polish chronicler and geographer of the 16th century, “the father of Polish cartography” Bernard Wapowski. For the historical cartography of East Europe this map is particular. After centuries of myths and occasional references the part of the continent appeared on the paper. As on a successful portrait of 16th century its shape is close to reality and inseparable from the epoch.

Bernard Wapowski was born about 1475 in Radochońce near Przemyśl in a wealthy family1. His surname originated from the village of Wapowce located not far from Radochońce. In 1493 he entered the University of Kraków where he obtained his bachelor's degree. He studied in the University in the same time with Nicolaus Copernicus. In 1500 Wapowski continued his studies at the University of Bologna, Italy, where he obtained in 1505 the master’s degree in laws. That very year he joined an embassy of the King of Poland Sigismund I to Rome to the court of the Pope Julius II. Rome in the early 16th century as one of centers of the European civilization granted to the scientist good opportunities for learning and contacts. Undoubtedly, Wapowski acquainted himself with all types of maps, among them the nautical charts (portolani) and medieval world maps (mappae mundi); the typical features of them he would use later when creating his own maps.

About 1506 Bernard Wapowski created his first map of the lands of the Kingdom of Poland which comprised the lands of Poland and Lithuania up to the Dniapro River (Dnipro, Dnieper). This manuscript map served as a basis for the cartographic representation of the corresponding area on the map of Central Europe by Marco Beneventano, 1507, and the map of Sarmatia by Martin Waldseemüller, 15132. Wapowski was familiar with contribution of his compatriots to the European cartography. On his manuscript map he marked two small villages owned by his family, Radochońce and Wapowce; that marks were transferred to the maps of Beneventano (see Fig. 1) and Waldseemüller. No doubt he knew that Jan Długosz had pointed his birthplace Brzeźnica among the geographical information about Poland and Lithuania given in 1449–1450 to the Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa. Later this information was included by Nicholas of Cusa to his famous map of Central and Eastern Europe3.

In 1515 Wapowski left Rome for good and returned to Kraków. Soon after his return he was made the King's secretary and received church benefice of canon of the Wawel cathedral. From 1526 to 1528 there is almost no mentions about him in historical documents apparently due to his work on the maps. Bernard Wapowski also is the author of the chronicle Dzieje Korony Polskiej i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego od roku 1380 do 1535, where the description of events before 1516 relied on historical works by Jan Długosz, Maciej Miechowita, Justus Ludwik Decjusz; for the years 1517–1535 he created his own description of the events.

About the maps created by Bernard Wapowski and the area included to these maps we learn from the text of the privilege (permission to print) granted by Sigismund I to the Kraków printer Florian Ungler. Here is a fragment of the privilege, dated October 18, 15264: “... duas Tabulas Cosmographie particulares, alteram videlicet nonnulla loca regni nostri Polonie et etiam Hungarie ac Valachie, Turcie, Tartarie et Mazovie (according to Stanisław Alexandrowicz5 Mazovie is an error, it should be Moscovie – T. G.), alteram vero Ducatus Prussie, Pomeranie, Samogitie et Magni Ducatus nostri Lithuanie continentem…”. In accordance with the privilege two woodcut maps were printed.

The first map by Wapowski was printed by Florian Ungler, as considered, in 15266; it was the map of Poland in the scale 1 : 1 000 000 named for it's scale the million map, milionówka. Fragments of this map representing a part of Greater Poland and Pomerania together with a part of Samogitia and East Prussia have survived.

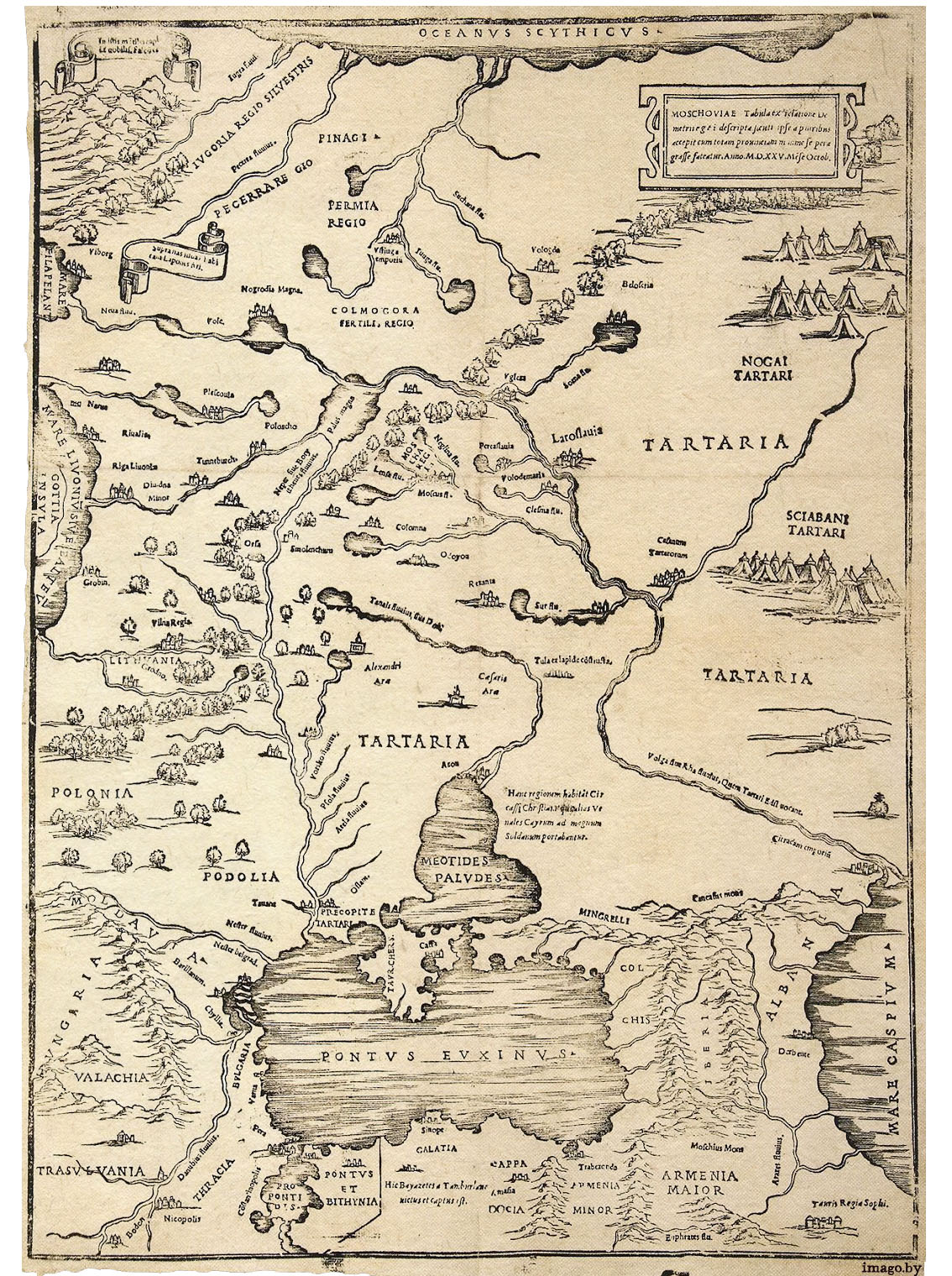

The precise name of the second map is unknown. Two slightly different names from different sources have reached our time. In the atlas by Abraham Ortelius Theatrum orbis terrarum, 15757, in the catalog of authors and their maps there is the entry: Florianus, Tabulam Sarmatiae, Regna Poloniae et Hungariae utriusque Valachiae, nec non Turciae, Tartariae, Moscoviae et Lithuaniae partem comprehendentem, Cracoviae 1528 – Mар by Florianus of Sapmatia, Kingdoms of Poland and Hungary with both Wallachias, with parts of Turkey, Tartary, Мuscovy and Lithuania, Kraków, 1528. The map Floriani Sarmatia, Polonia, Hungaria, utraque Valachia, Turcia, Tataria, Moscovia, Lituania – Sarmatia, Poland, Hungary, both Wallachias8, Turkey, Tartary, Muscovy, Lithuania [by Florian] with the date 1528 was mentioned in the catalog by Floris Romer composed in Budapest in 1861–18629. For this map the shortened name is accepted as the map of Sarmatia, and the two parts of which it consists, are conventionally called as the maps of South and North Sarmatia. The size of two parts put together was 60 Х 90 centimeters without the margins, the scale is about 1 : 2 900 000.

No copy of the northern part of the map has survived to our time. According to the reconstruction10 the northern part shows the eastern part of Pomerania, East Prussia, Samogitia, Lithuania proper, Livonia, the north-eastern part of the Grand Duchy of Muscovy, and, probably, the south-eastern strip of Sweden.

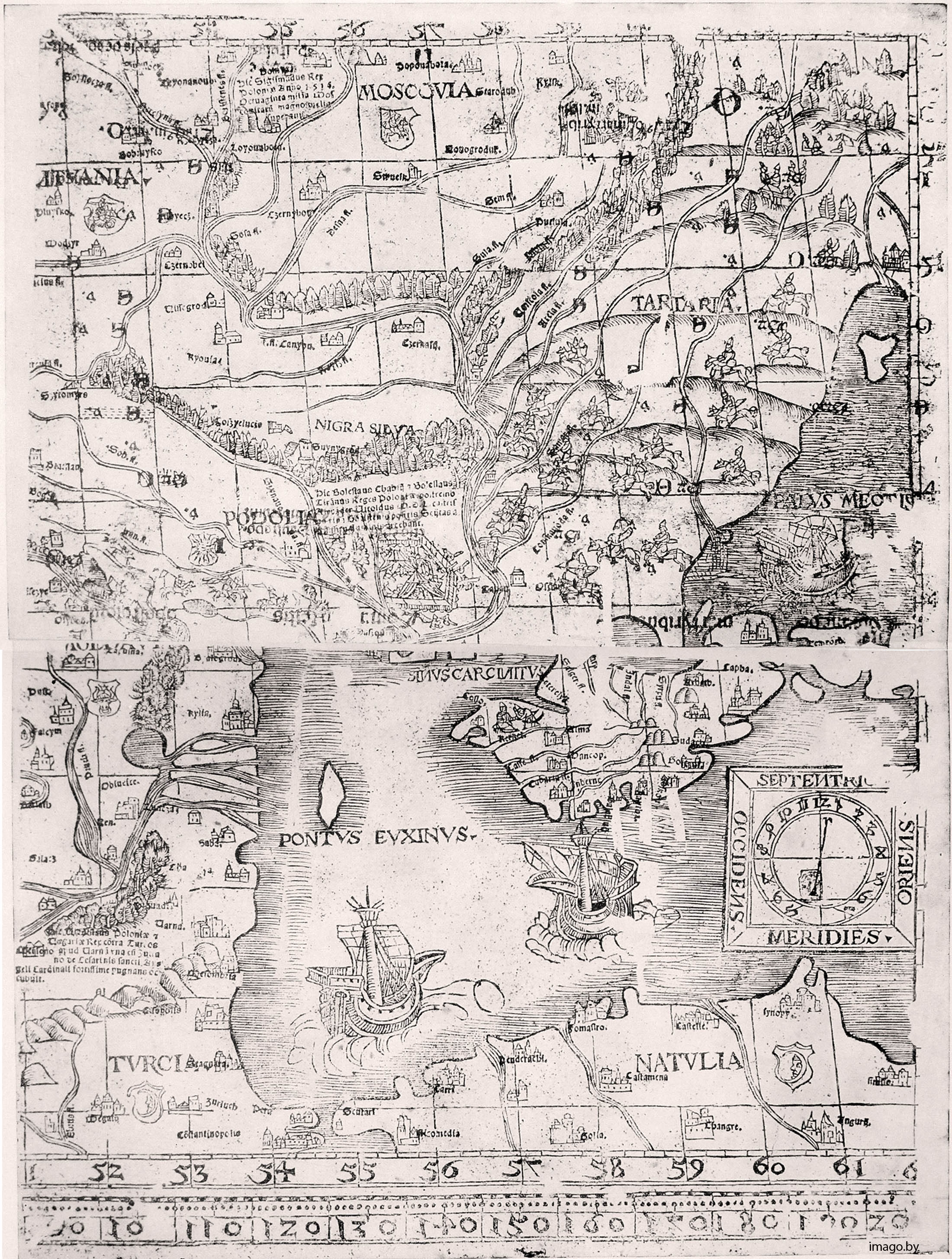

Fragments of the maps of Poland and South Sarmatia were accidentally found by Kazimierz Piekarski in 1932 in the Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw (Archiwum Glówne Akt Dawnych). They were used as the cover of a ledger of the salt mine from the town of Bochnia. The map of South Sarmatia had been printed from four wooden blocks, the prints of two of them have survived11. These fragments include the southern part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Crimean Khanate, other lands along the perimeter of the Black and Azov seas, especially the northern part of the Anatolian peninsula and a part of the territory of the Grand Duchy of Muscovy (see Fig. 2).

The woodcut was combined with metal type used to print the smaller place-names and captions. These were printed in a second printing12. On the fragments of map of South Sarmatia multiple prints of single letters and fragments of lines overlapping some elements of the map capture the attention. Some names of settlements and rivers exceed their pictograms. Such “negligent” graphical representation is not incident to the surviving fragments of the map of Poland. That’s why according to Karol Buczek, these fragments are considered to be the proof print of the map13.

The only trustworthy edition of the map of South Sarmatia is the edition of 1528 because it was twice mentioned in the catalogs of maps (see text above). From the letters of the theologian Johann Hess to the mathematician and astronomer Willibald Pirckheimer, dated May 11 and July 13, 1529, we learn that not long before writing them two “inelegant” maps of Sarmatia and Scythia had been published in Kraków14. Despite the documentary evidence of the year 1528 there is an opinion that two editions of the map were printed, the first edition was printed in 1526 or slightly after 1526, the second one was in 1528. It is considered that the extant fragments belong to the first edition and the reason of the second edition, in 1528, was taking into account by Bernard Wapowski the additional information from new sources15.

The main reason that both maps have been almost lost is the great fire in Kraków in 1528 that destroyed the printing office of Florian Ungler. The originals of the fragments of maps were burned in 1945 in Kraków during the Second World War, so now researchers are working with their copies16.

In 1533 Wapowski worked on the new map of northern Europe: Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Muscovy and Livonia, but did not finish it. He died in Kraków in November, 1535.

Before proceeding with the detail review of the map let's look how the term Sarmatia, used in the title of the map, changed over time.

The term Sarmatia comes from the name of a group of the nomadic Iranian tribes of Sarmatians (Sauromates) who from 3th century B.C. to 2th century A.D. lived in the Black Sea steppes and played an important role on the international arena; they were driven west in the next two centuries by the invasions of Goths and Huns. The tradition to call Slavs or some Slavic peoples (Poles, Czechs) Sarmatians and their territory Sarmatia lasted for a long time. Tadeusz Ulewicz gathered evidences about use of the name Sarmatia concerning the territories “inter Germaniam et Meotides paludes” by German, French and English chroniclers at least from the 9th century17.

In the 13th–15th centuries in Byzantium there became popular Geography – a treatise by a scientist of the 2nd century A.D. Ptolemy from Alexandria, which was a textual description of the map of the world showed the geographical objects with their coordinates. This book was brought from Byzantium to Western Europe in the early 15th century, translated into Latin and published in 1464 for the first time without maps. From the 1470's the edition was supplemented with “classical” maps based on the text description. The later numerous publications of Geography were complemented by the modern maps, and the “classical” maps were introduced along with the Ptolemaic place names with the modern ones. The Geography by Ptolemy discerned European and Asian Sarmatia. European Sarmatia covered the territory from the Vistula (the Wisła River) to the Don, from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Asian Sarmatia stretched from the Don to the Volga River in the east and to the mythical Hyperborean mountains in the north.

The European chronicle tradition and spreading of modernized versions of the Geography promoted the “Sarmatian” terminology in the writings of European scholars. Jan Długosz in his chronicle Annales seu cronicae incliti Regni Poloniae… created in 1460–1480 widely used the toponyms from the work of Ptolemy. Maciej Miechowita in his Tractatus de duabus Sarmatiis (Treatise on the Two Sarmatias), printed in 1517, described European and Asian Sarmatia within the limits set by Ptolemy. The map by Martin Waldseemüller, 1513, which included the data by Wapowski – Sarmatia Evr/opeae/ sive Hungarie, Polonie, Russie, Prussie et Valachie – identified European Sarmatia with Poland, Rus’18, Prussia, Hungary, Wallachia. In the same time (the end of the 15th – beginning of the 16th century) the name Sarmatia started to be applied in respect of Poland and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Pol. Rzeczpospolita), which included territories of Poland and Lithuania. So Hartmann Schedel in the treatise Chronicon Mundi… printed in 1493, noted that King Władysław Jagiełło “lituanosac russitas ad regnum Sarmacie adiunxit”, that is to say attached Lithuanians and Rusyns to the Sarmatian kingdom19.

It's hard to say how the preserved names of the map by Bernard Wapowski match the original, because in them Sarmatia is separated by comma with the names of states and territories. In 1530 Wapowski wrote in a letter to the bishop Joannes Dantiscus about two maps of Sarmatia sent by him to Johann Eck. In the abovementioned letters of Hess to Pirckheimer the map by Wapowski was named as the map of Sarmatia and Scythia. Since the name of Scythia is missing on the surviving fragments of the map, Karol Buczek suggested that this word had appeared in the second edition of the map in 152820. But it is worth to note that at the beginning of the 16th century among European scientists the name Scythians as a synonym for the Tartars, i.e. all Turkic speaking peoples21, was in common use. On the map by Wapowski in the inscription placed below the Black Forest (Silva Nigra), the Tatars, enemies of Vytautas, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, were named as Scythians22. It seems that the toponym Sаrmatia was used by Wapowski and his correspondents for the lands within the boundaries of the Ptolemean European Sarmatia as the collective name of the countries that opposed the “Scythians“, i.e. Tatars.

Research of the map of Sarmatia by Bernard Wapowski began long before its finding in 1932, because historians understood its importance for the development of European cartography. Veniamin Kordt mentioned the maps by Wapowski in his Materials on History of Russian Cartography23. The Ukrainian scientist Fedir Petrun’ created a table of “genesis” of representations of the territory of Ukraine by European cartographers from the first quarter of the 16th century to the first third of the 17th century, for which just the maps by Wapowski are the starting point24.

The leading role in the introduction of new-founded maps by Bernard Wapowski into the scientific circulation and in the history of European cartography has been played by the Polish researcher Karol Buczek. It was he who published an article about the geographical research in the works of Jan Długosz and Bernard Wapowski as the beginning of Polish cartography, where he gave the description of the map25. Just the copies of maps contained in the edition Monumenta Poloniae Cartographica (see footnote 14) prepared by Buczek have survived. The analysis of maps by Wapowski in the context of development of Polish and European cartography has been performed by Buczek in the fundamental work Dzieje kartografii polskiej od XV do XVIII wieku (edition in English The History of Polish Cartography from the 15th to the 18th century26); in the annex to this work the fragments of map of Sarmatia were published for the first time.

Stanisław Alexandrowicz continued studying all aspects of creation and use of the maps by Bernard Wapowski considering the new information that had been found and published in two decades passed since the research of Karol Buczek27. Also he regarded the map of Sarmatia in the context of fight of European states against the Turkish and Tatar expansion in the 15th – 17th centuries28.

The maps by Wapowski had a decisive impact on the image of Eastern Europe in European cartography for more than 100 years. The map of South Sarmatia created the image of the territories, which with minimal changes and simplifications had been kept in European cartography: for Grand Dutchy of Lithuania until Radziwiłł’s map of the early 17th century, for centre and south of Ukraine until the maps by Beauplan in the middle of the 17th century. The map of Sarmatia or its parts were used, inter alios, by29 :

– Henryk Zell during the preparation of his Europe map in 153530. Wapowski personally was not acquainted with Zell, but could have collaborated with him through the mediation of Copernicus;

– Sebastian Münster. Buczek considered that the map POLONIA ET VNGARIA XV. NOVA TABVLA, which was placed by Münster in Basel edition of the Ptolemy's Geography, 154031, was based with considerable simplification on the map of Sarmatia, 1528. This simplification, by the example of the Crimea, means that from twenty place names on the map by Wapowski only four left on the map by Münster. Münster also made on his maps the graphic emphasis shifted in comparison with the original. On the map by Wapowski the Black Sea with the Turkish coast is one of the centres of interest. On the map by Münster the Black Sea was partly placed at the periphery of the map. This map was reprinted in the later editions of Ptolemy's Geography and in the Münster's Cosmography of 1544;

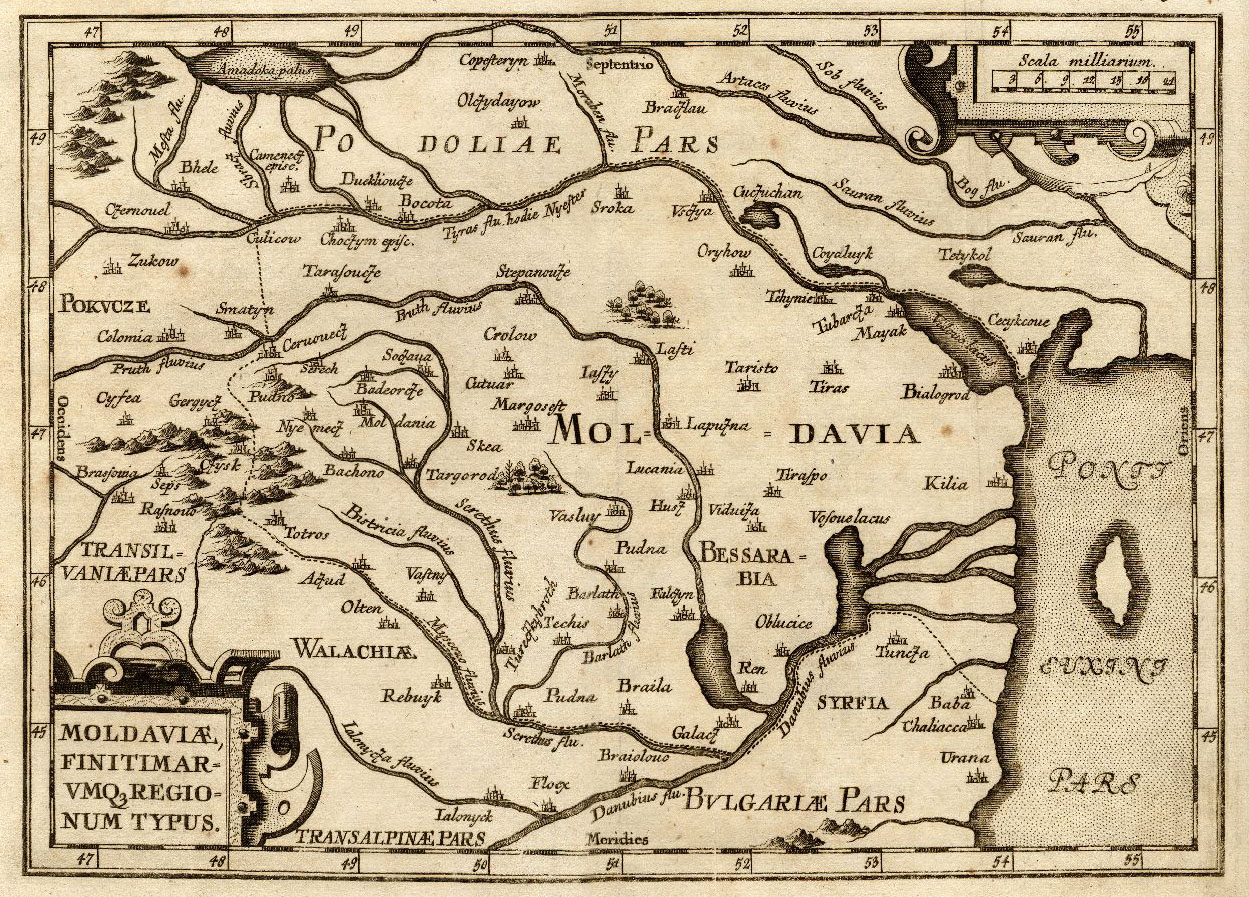

– Georg von Reichersdorff. His map of areas of present-day Moldova, Romania and Bulgaria in the book Moldaviae quae olim Daciae pars, chorographia, Georgio a Reichersdorf Transilvano auctore, published in Vienna in 1541, is more in detail than the map by Münster;

– Gerardus Mercator. He used the map of Sarmatia when creating a globe of the Earth in 1541, the famous map of Europe in 1554 and its improved version in 157232. It also concerned the map of Lithuania, which was printed in editions of the atlas by Rumold, the son of Gerardus Mercator, from 1595 to 163033. It’s interesting that on the map of Europe, 1554, Mercator did not take into account the innovative image of the Crimea on the map by Wapowski (which will be considered later in the article). This incorporation partially took place only on the map Tauricia Chersonesus Nostra aetate Przecopsca et Gazara − Chersonesus Taurica, now called Perekop or Gazara, that was first published in the atlases of Gerardus Mercator during his lifetime in 1585 and 1589 and in the atlas amended by Rumold Mercator in 159534;

– Giacomo Gastaldi. It is considered that he used the maps by Wapowski during the preparation of his own maps since 1546.

The famous reduced and altered version of the maps by Wapowski was made in 1558 by the Polish cartographer Wacław Grodziecki (Grodecki)35. The territory of the East Europe is shown with use of the maps by Wapowski in the аtlases by Abraham Ortelius (from 1570), Gerard de Jode (1562–1593) and their followers.

Studies on the map of Sarmatia by Bernard Wapowski should be complemented with a detailed analysis of the toponyms on the map. The author tries to perform such an analysis, especially for the territory of present-day Ukraine.

First of all we note that almost nothing remains of the Ptolemy's Sarmatia on the map of Sarmatia by Wapowski. “Tabula Sarmatiae secunda (map of the North Sarmatia – T. G.) unfortunately does not see Ptolemy” – this is a citation from the mentioned letter from Hess to Pirckheimer36. The same statement can be applied to the map of South Sarmatia. On the map by Münster Poloniae et Ungariae… two “Ptolemy’s” lakes are shown: Chronos Lacus and Amadoсa Palus, that’s why those lakes were shown on the original map. On the surviving fragments of the map the shape of the Black and Azov Seas is typically Ptolemy’s, but no other toponyms borrowed from the Geography are presented.

Let’s look on the upper of two fragments of the map (Fig. 2). This fragment include the large part of the territory of Ukraine and the part of lands of Belarus and Russia.

One of the innovations of the map of South Sarmatia is representation of the river system of Dniapro37. In the geographical description from the chronicle of Jan Długosz38 among the “seven main rivers of Poland” the Dniapro River, the Pripyat River with its tributaries Teteriv and Berezina, the Ros River and Southern Bug (Boh) that “disembogues into the Dniapro River near the castle and town of Dashev” are mentioned. All of them are shown on the map, besides them the rivers Svislach (Soyisloczo fl.), Seym (Sem fl.), Sozh (Sosa fl.), Tiasmyn (without the name on the map), Sob (Sob fl.), Savranka (Savran fl.), Syniukha (Szynouoda fl.), Molochna (that flows into the Sea of Azov, without the name on the map) are shown for the first time, and also the left tributaries of Dniapro, i.e. Sula (Sula fl.), Psel (Psiola fl.), Vorskla (Vorskola fl.), Oril (Arela fl.), Samara (Samara fl.) and Kinski Vody or Konka River (Konskavoda fl.).

The island Tavan on the Dniapro – the well-known place of river-crossing – and the stronghold of Islam Kermen (Osslam) built by the Crimean Khan Mengli Giray in 1504 are shown. There are interesting marks of two fortifications without names on the left bank of the Dniapro River upstream from Tavan. They are possible marks of the river-crossings. The treatise De moribus tartarorum, lituanorum et moscorum – On the Customs of Tatars, Lithuanians and Muscovites by Michalon Lituanus, 1550, contains the list of Dniapro river-crossings: “The crossing downstream from Cherkasy (Cirkassi)is possible only in several places. They (crossings – Т. G.) are named as Kremenchuk (Kermieczik), Upsk (Upsk), Herberdiiev Rih (Hierbedeiewrog), Mashchuryn (Massurin), Kochkosh (Koczkosh), Тovan (Towany), Burkhun (Burhun), Тiahynia (Tyachinia), Оchakiv”39. According to this list the upper fortification is likely to be the first cartographic designation of the present-day city of Kremenchuk40, Ukraine. The middle crossing can be identified with Upsk, which now is not localised.

Tavan, Islam Kermen and the left tributaries of the Dniapro River were shown for the first time on a map by the Genoese cartographer Battista Agnese in 1525. This map was created by Agnese on the basis of the data received from Dmitry Gerasimov, an ambassador by Basil III, the Grand Duke of Moscow, who stayed in Rome in June–July, 152541. It is doubtful whether this map was a model for Wapowski for designation of the left tributaries of Dniapro. A special feature of the map of Sarmatia is designation of the headwaters of the left tributaries of Dniapro more eastward or beyond the boundaries of the map. Wapowski had information about the embouchures of the left tributaries and about the direction of their flows, but he knew nothing about their springheads. Such a circumstance excludes copying from the map by Agnese, where the coordinates of heads of these rivers were pointed more correctly.

The four parts of the “upper” fragment of the map are denoted by the inscriptions LITUANIA, MOSCOVIA, PODOLIA and TARTARIA. On the territory marked as TARTARIA sketches of nomadic life are depicted and no stationary settlements are shown there. The exception is Tana/Аzov/Azak (the mark without name in the mouth of the Don River) and the settlement of Temriuk (Temröch) on the Taman peninsula. As Evliya Çelebi informed, the fortress of Temriuk was founded by the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Selim I in 1515–1516 and finished in 1525 by the Sultan Suleiman I42. It's appearance on the map approximately after 1526 evidenced that the tactical information about the territories under the control of the Ottoman Empire or Crimea was available to Wapowski.

| On the lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (LITUANIA region) such toponyms can be read: Svislach (Soyisloczo), Mozyr (Modsyr), Hlusk (Gluysko), Babruysk (Bobruysco), Rečyca (Rzecytsa), Homiel (Homel), Loyova Hora i.e. Loyew (Loyovahora), Chornobyl (Czernobel), Vyshhorod (Vissegrod), Kyiv (Kyovia) settled on the right and left banks of the Dniapro River, Kaniv (Canyov), Cherkasy (Czerkasy). Among these objects only the Dniapro River, Kyiv, Kaniv and Cherkasy were shown on the maps before, all the other objects were shown for the first time. The settlement between Svislach, Rečyca and Homiel remains unidentified. Alexandrowicz read this name as Tajmanow (Tayonanoua)43, Bagrow as Tajona noja44, but there are no data about settlements with similar names in the 16th century. |

In the MOSCOVIA region there are the settlements Novhorod-Siverskyi (Novogrodus), Chernihiv and for the first time, Popova Hora (Popovahora), Starodub (Starodub), Rylsk (Rylsk), Putyvl (Putivl). The settlement being approximately on the place of the present village of Sosnytsia, Chernihiv oblast (region) of Ukraine, is unidentified. Leo Bagrow has read this name as Swest45 but there is no information about the real place with this name.

From the location of the inscription PODOLIA it can be concluded that the cartographer used this name for a large part of the Right-Bank Ukraine. This territory conditionally began on the south from the Tiasmyn River (the river without name shown under Nigra Silva – The Black Forest). The town of Bratslav (Braslav) was depicted, and, for the first time, the Tiligul lake (without name on the map), Ustie (Uczye) and Orhei (indecipherable inscription lower than Ustie) on the right bank of the Dniester River.

There is a visible “corridor” between the Dniester and Savranka rivers on which the army moved to the lower reaches of Dniapro. This corridor can be identified with the old trade route that led from Western Europe via Lviv and the divide between the Dniester and the Southern Buh rivers to Dashev (or Daszov, now Ochakiv). A part of this route on the lands of present Ukraine from the middle of the 16th century is known as Kuchmanskyi shliakh (route). The name of a ruin shown between the Dniester and Savranka rivers can be read with the help of map by Münster, 1540, as Kuchurgan (now a village in the Odesa oblast, Ukraine).

The unnamed ruins near the confluence of Syniukha and Buh rivers were mentioned by Marcin Broniowski in Tartariae Descriptio, 1579, as the ruined town Kodyma46. In European cartography of the first half of the 16th–17th centuries these ruins as a result of copying coincided with name of Syniukha River (Szynouoda fl.), which led to appearance on maps of the settlement Synia Woda, that has never really existed.

There is a tradition among historians to "bind" all mentions about the Right-Bank settlement named Zvenyhorod in the historical sources of the 14th–16th centuries to the Zvenyhorodka town in Cherkasy oblast, Ukraine. But Zvenyhorod (Suynygrod) on the map by Wapowski was indicated considerably lower than the Tiasmyn River, on this place it was shown on maps until the middle of the 17th century. Zvenyhorodka town in Cherkasy oblast is placed upper the Тiasmyn River and the history of this settlement is documented since the beginning of the 17th century. That’s why the settlement named Zvenyhorod can also be considered as not identified.

Between the springheads of the Tiasmyn River and Syniukha River the ruins are shown with the name that passed to the European maps of the 16th–17th centuries in the form of Cosidan, Coszidan, Coszidanz. Since there are no historical evidence of existence of such a settlement, the author revised the reading of this name and made the conclusion that it could be read as Coszyeluczo – Kościelec. But that name is also not found in Podolia and other Right-Bank Ukraine. The name Coszyeluczo could be related to the family of Kościelecki, representatives of nobility, who held senior positions in the Kingdom of Poland. Their hereditary nest Kościelec is far enough from Ukraine – near Inowrocław in the North Poland. At the beginning of the 16th century the most known representative of the family was Andrzej Kościelecki, who brought up Beata, an illegitimate child of the King Sigismund I as his own daughter. After the death of Andrzej in 1515 his estates and custody of Beata passed to his brother Stanisław, the voivode (governor) of Sieradź, Kalisz and Poznań. Stanisław Kościelecki was acquainted with representatives of the humanitarian Polish elite Piotr Tomicki and Jan Dantyszek (Johannes Dantiscus), the latter was a friend of Bernard Wapowski, but nothing is known about communication of Bernard Wapowski with Stanisław Kościelecki. Shortly after creation of the map the destiny of Kościelecki family was united with the lands shown on the map: in 1539 Beata Kościelecka for a short time was the wife of a son of Kostiantyn Ostrozkyi (Konstanty Ostrogski), Ilia (Eliasz), who had the title of starosta (governor) of Bratslav and Vinnytsia. One can assume that the indication of Kościelec on the right bank of Dniapro is reflection of some political intrigues or projects of the beginning of the 16th century, unknown nowadays.

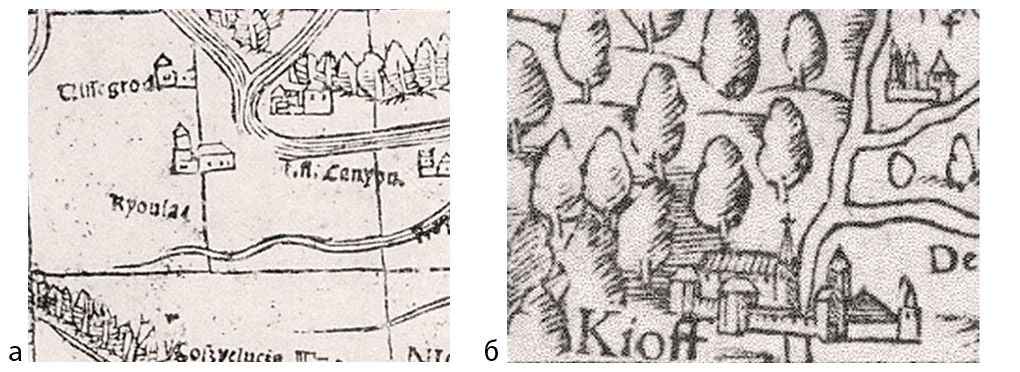

Doubling or ever tripling of the same name is often observed on old maps. There are three marks of Kyiv on the well-known map by Fra Mauro, 1459. One of them – Chiovio – is on the right bank of the Dniapro River, two: Chievo over chio and Macharmi47 are on the left bank. The last name is a variant of the Turkish name of Kyiv Mankermen (means large fortress), that besides the usual name was used in the 14th –16th centuries48.

In the first half of the 16th century several maps where Kyiv is shown on the right and on the left banks of the Dniapro River appeared: map of Sarmatia by Wapowski; maps of Europe by Mercator since 1554, map of Muscovy from the Cosmography by Münster, 155049. Let's look at the origin of the Left-bank mark of Kyiv on these maps.

On all the maps of Europe created by Mercator since 1554 the Left-bank mark of Kyiv originated from the map of Sarmatia by Wapowski (see Fig. 5а). During the process of copying the Right-Bank name – Kioua – was repeated near the Left-bank mark. The letter K as a result of copying transferred into the letter R. In that way on the left bank of Dniapro on the half way between Kyiv and Cherkasy the settlement Rioua appeared.

It is known that the map of Muscovy from the Cosmography by Sebastian Münster, 1550, was based on the information by Ivan Liatskii, a Muscovite voivode who emigrated to Lithuania for political reasons in 1533. This information Münster had received from Anthony Wied, about which he gratefully wrote in his Cosmography.

The lower part of the map of Muscovy by Anthony Wied50 contains two inscriptions: in old Ruthenian language dated 1542 and in Latin dated 1555. The Latin text mentioned that Ivan Liatskii had helped to the author to create the map. Leo Bagrow considered that the manuscript map had been made by Wied in 1542 and 1555 is the year of engraving the map51. On the contrary Alexandrowicz proved that the map has been created in 1535 (1555 is an error of the engraver) and printed in 154252. The pictures of Kyiv on the both maps are almost similar but on the map by Wied the picture was placed along the Dniapro River, and on the map by Münster it united the right and left banks (Fig. 5b).

To the author's knowledge no comparison of toponyms on the map of Sarmatia by Bernard Wapowski and the map of Muscovy by Antony Wied has been carried out. Only Alexandrowicz has noticed that the map of Wied on the border lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania brings nothing new to the image created by Wapowski, but only deforms it. He has also noticed the copying of particular objects from the map by Wapowski to the map by Wied53.

On the both maps in the parts that coincide the toponyms are similar:

The map of Sarmatia by Bernard Wapowski:Kyiv, Vyshgorod (for the first time), Chornobyl (for the first time), Liubech (for the first time), Rečyca (for the first time), non-identified settlement, inscription about the battle of Orsha, Loyova Hora (for the first time), Homiel (for the first time), the Sozh River (for the first time), Chernihiv, non-identified settlement, Starodub (for the first time), Novhorod-Siverskyi (for the first time), the Seym River (for the first time), Putivl (for the first time), Azov (without name on the map).

The map of Muscovy by Anthony Wied:Kyiv, Rečyca, inscription about the battle of Orsha (with the picture), Homiel, Sozh, Chernihiv, Starodub, Novhorod-Siverskyi, Seym, Putivl, Azov.

The similarity of the images on the both maps forces to seek the single source of the information for the both maps. Evidently this source of information was abovementioned Ivan Liatskii who stayed with the Muscovite embassy at the court of the King of Poland Sigismund I from the end of January since April, 152754. At the same time Bernard Wapowski has worked intensively on the map of Sarmatia using all possible sources of information.

A special feature of the maps by Wapowski and Wied are the text messages about the battle of Orsha, 1514. The battle took place between the allied forces of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Kingdom of Poland, and the army of the Grand Duchy of Muscovy, that was defeated. On the map by Wapowski the text Ніс Sigismundus Rex Poloniae Anno 1514 Octuaginta milia Moscovitarum magno vectigalis(?) superavit is placed. The map by Wied contains the short text: Conflictus an: 1514. The battle on Orsha has long been an area of special interest by Bernard Wapowski. In 1515, during his stay in Rome, he wrote a panegyric verse in honour of the victory of Polish weapon in this battle55. It seems that this battle was marked on the map at the initiative of Wapowski, not Liatskii.

We can suppose that it was known among European geographers that Ivan Liatskii had already provided the information for the map by Wapowski. That’s why Anthony Wied in 1535 appealed to Liatskii with the second request after the main edition of the map with this information was destroyed.

Acceptance of Ivan Liatskii as one of the providers of data for the map of Sarmatia permits to clarify the question about dating of the map and number of its editions. Кarol Buczek, who was the first who wrote about the maps by Wapowski, considered that the map of Sarmatia had been published “not earlier than 1526”56; further the cautious “not earlier than” was often ignored. Including the information received in January–April, 1527, to the map of Sarmatia means that this map was created not earlier than 1527. So far as only the edition of map in 1528 is documentarily evidenced, it’s worth to support the point of view that there was no earlier editions of the map and the survived fragments belong to the single proof print.

Let's return to the Left-bank mark of Kyiv on the maps. On the map of Sarmatia by Wapowski and the map of Muscovy by Münster that was based on the information by Ivan Liatskii Кyiv has particular features: on the right bank a church is pictured, on the left bank – a secular building. This picture could have reflected the real role of the Left-Bank settlement in the political life in Kyiv.

In the chronicles of Kievan Rus’ of 11th– the beginning of the 13th centuries the Gorodets settlement placed on the Left-Bank historical place Myloslavichy is mentioned57 (now Myloslavichy included to the territory of Kyiv). In the “Spisok gorodov russkikh, daliokikh i blizkikh” (“The list of Rus’ towns, far and close”), dated by the end of the 14th– beginning of the 15th centuries, among the “Kyivan towns” the settlement Miroslavitsi is mentioned58. At the time it was the out-of-town residence of Kyiv rulers. The Left-bank settlement became really visible in the political life of Kyiv in the second half of the 15th century where the Prince Simeon Olelkovich resided and ruled from there.

Simeon Olelkovich59 (1418 – 1470), the last ruler of the Principality of Kyiv (from 1455), the great grandson of Algirdas (Olgierd), the Grand Duke of Lithuania, was a powerful figure of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and a successful governor who defended his lands from the invasion of Tatars. Because of the political power he was mentioned with the title of “tsar” in the Moldavian chronicles of 15th–16th centuries60. The days of his principality of Kiev are considered a cultural renaissance, particularly the prince renewed the Holy Dormition Cloister of Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra that had suffered during the Mongol invasion in 1240. Historical evidences about the location of the former residence of Simeon Olelkovich were collected by the archaeologist Viktor Hoshkevich61. Historical documents contain enough topographical details to restore the place of setllement which was explored in 189062 and in the 20th century63.

Let us begin the review of the “lower” fragment of the map of South Sarmatia with the image of the Crimea because of the precision and detailedness, unique for the European cartography of the 16th century.

At first let's look to representations of the Crimea on the maps created by European cartographers before 1527. Today there is no separate study on the evolution of historical maps of the Crimea. The oldest map of the Crimea is a fragment of a Greek manuscript of Geography by Ptolemy, 13th century, which is kept in the Topkapi Palace Library in Istanbul, as indicated in Leo Bagrow’s addition to the article by H. Kohlin. The portolani of the 14th−16th centuries and the "round" Crimea on the map by Jacob von Sandrart, 1687, are named by Bagrow the next stages of mapping the Crimea64. The publication of a collection of maps of the Azov and Black Seas, which can trace the development of mapping the Crimea, made by Anton Gordeev is worth mentioning65.

Maps representing the Crimea in the 14th – early 16th centuries could be classified into two large groups: the portolan charts and maps of the Ptolemy tradition. Shapes of the coastline of the Black and Azov Seas and the Crimea on the sea nautical charts are practically perfect. The particular attention was paid to inhabited places on the coast, but no settlement in the heart of the Crimean Peninsula was represented on the portolan charts. The Black, Azov Seas and the Crimea have common characteristics on all maps based on the text description from the Geography by Ptolemy, starting from the map found by Bagrow to the maps published in the middle of the 16th century. The Crimea on them has a “triangular” (by Bagrow) form, the only river (Istrian) and settlements in accordance with the list and coordinates contained in the Chapter 6 of the Book III of Geography are marked on its territory.

The first attempt of combination of the "Ptolemy" maps and portolan charts was made by Nicholas of Cusa (see Eichstätt map, 149166). On this map the names are typical to the portolani: Caffa, Soldea, Cimbab, Lemita, Dospera; and they were marked on the typical "Ptolemy" outlines of the Crimea. The Goths Principality with the capital of Theodoro and a settlement in the heart of the peninsula called Gzungari are marked only on this map. The Eichstätt map, 1491, can be considered as the most “modern” predecessor of representation of the Crimea on the map by Wapowski.

Let us consider the Crimea on the map by Wapowski (Fig. 7). The peculiarities of this cartographic representation are the following:

– the original contour of the Crimea, nothing of its kind was met on any of European maps;

– the completeness of representation of the Crimea river system, unique for West-European cartography till the 18th century. The main rivers of the Crimea: Salgyr (Salger fl.), Indol (Indal fl.), Churiuk-Su (Syrcu fl.), Chornaya River (without a name on the map), Belbek (Cubarta fl. – old name of the river), Kacha (Casse fl.), Alma (without a name on the map) are marked. Such details set us even more wondering, if we take into consideration that by the European standards these rivers are not significant: "Belbek as well as Kacha, Alma and Salgyr are considered among the biggest rivers of the Crimean Peninsula, but they are not big if compare with rivers depicted on the other part of the map"67;

– the toponymic net of settlements, which fully corresponds to its time. Land toponyms of the Crimea will be discussed in more details further.

Arabat (Arbath) is marked to the right of the mouth of the river of Churiuk-Su. Foundation of this fortress is dated to the middle of the 17th century according to Evliya Çelebi68. But Arabat existed at the time of the Turkish conquest of the peninsula. That is evidenced by the mark of Arabat as a significant settlement in the early 16th century on the map by Wapowski.

The notation of Kaffa (Cabha) is not new, since it in the different transcriptions was marked on the portolan charts. In the Middle Ages, Sudak (Sudach) was better known in Europe under the names Suhdaia, Soldaia, Sodaia, Soldaja on the portolan charts, and under the name of Surozh in Muscovite documents.

Two previous toponyms are well-known, which cannot be said about the toponym, located on the coast to South of Sudak. It reads as Solsou and can be considered the pronunciation by a foreigner of the words Suuk-Su ("cold water" in Tatar) – a common Crimean hydronym. Now it is impossible to identify it with a real settlement. The mediaeval town of Solkhat on the map of Wapowski is marked for the first time, and with the Tatar version of the name Crym. Mangup (Mancop), which completely lost its value as a town only after the fire in 1592 or 1593, and Kerkel also were marked on the map for the first time. Kerkel was the main quarters of the Crimean Khan as evidenced by the sketch of worshiping the Khan depicted next to Kerkel. The summer residences of the Crimean khans Alma, Inkerman (Inberne) and Hezlevi (Coslo) are marked for the first time.

Several Crimean toponyms are marked only on the map by Wapowski; they were not marked earlier or moved from this map to the later maps. It is the abovementioned Solsou and three lighthouses69 on the Southern coast: Abskow, Knytha, the third name could not be read. The name Knytha may have derived from the Scandinavian name Knyth. Coterelyz (?) (there are names of Greek origin with similar sounding Simeiz, Kikineiz in the Crimea), which is probably the “pretatar” name of the lake of Donuzlav, marked on the map as a gulf, belongs to the same group of names.

Representation of the Crimea on the map by Wapowski indicates that it is not a compilation of previously created texts or maps, but a completely original work.

The material (cartographic or textual) was likely to be gathered specially for this map, and perhaps had the military intelligence origin. There were two informational sources to create the map of the Crimea. The first of the sources provided information on the hydrographic system of the peninsula and the settlements away from the coast. It provided the data about Crym, Mancop, Sudach, Alma, Inberne and about the rivers. Use of eastern versions of the names, such as Crym, Sudach, may indicate a non-European (possibly Tatar or Turkish) origin of this source of information. The second source is a result of voyages near the coast of the Crimea. It provided the data on now unknown lighthouses seen from the sea and, possibly, about Solsou, Coterelyz, Coslo (coastal names misspelled by a foreigner).

Upper in the article we mentioned that Bernard Wapowski during his stay in Rome send his map of Polish and Lithuanian lands to two groups of cartographers − in Rome and Strasbourg − which independently worked on the new editions of the Geography by Ptolemy70. Since the publication in Strasbourg took place in 1513, six years later than the publication in Rome, there is perception that the image of Eastern Europe in the Strasbourg edition (on the map by Martin Waldseemüller) is an amendment to the Roman edition rather than the original product71. But there are arguments in favor of the direct links of Wapowski with Strasbourg72. On the map of Sarmatia the Anatolian peninsula (NATVLIA), belonging to the Ottoman Empire, and a part of the Balkan peninsula (TVRCIA) is shown by Wapowski on the basis of modern maps from the abovementioned Strasbourg edition of Ptolemy's Geography, 151373.

The Anatolian peninsula is shown by Wapowski on the basis of the map Tabula Nova Asie Minoris from Geography, 1513 (see Fig. 8a, 8b). This map in comparison with the previous editions of Georgaphy represents a renovated network of settlements on the peninsula. Turkish towns and settlements on the coast of the Black Sea are shown on the basis of the portolan charts: Nicomedia (Izmit), Scutari (Ūsküdar), Carpi (Kerpe), Penderachia (Eregli), Samastro (Amasra), Castelle (Cide), Synopy (Sinop), Simisso (Samsun)74. The real names of existing towns on the inner territories instead of Ptolemy's towns also were transferred from the Tabula...,1513: Bolla, Kastamеnа (the present-day towns Bolu and Kastamonu), Changre, Zoguru (possible towns of Kargi and Chorum)75. Following the principle of detailed depiction of the river system Wapowski supplemented the map with rivers. One of them without name near Penderachia can be identified with the Sakarya River, marked in the Tabula..., 1513, as Zangar. The second river near Somastro may be the Filyos River, named as Thio in portolani76.

The territory of the Balkan Peninsula until to the symbolic picture of mountain ridge was pictured by Wapowski using the map Tabula Moderna Borsine, Servia, Greciae et Sclavonie from the same Strasbourg edition of Gеоgraphy, 1513 (see Fig. 9a, 9b). The mountain ridge and the confluence of two rivers into the Maritsa River (the Greek name of this river Evros is used) transferred from this map. This can be said about Mexember (Mesemvria, the present-day Nesebar, Bulgaria), Sixopolis (Sozopol? – Т. G.), Stagnara (the bay of Igneada)77, Pera and Constantinopolis. The mark Megalo can be identified with the Turkish town of Malkara. The toponym Zurluch is marked for the first time and means the Turkish settlement Ģorlu.

Bernard Wapowski used the reduced number of coastal settlements from the both abovementioned maps – only the main ones, that generally were marked on the portolan charts in red colour78. But the both maps, Tabula Nova Asie Minoris and Tabula Moderna Borsine, Servia, Greciae et Sclavonie, has no color distinctions in toponyms. That’s why we shall suggest that Bernard Wapowski was not only a user, but one of the providers of information for these maps.

After the analysis of the images of modern Romania and Moldavia on the map of Sarmatia it can be concluded that Wapowski used only the new information specially gathered for this map. Perhaps he used the text descriptions of travels, particularly from Poland to Constantinople. The King's ambassador Andrzej Bzicki who travelled from Belz to Constantinople in 1557 mentioned Obluchitsa (Oblucice, the fortress near the town Isaccea, Moldova), the crossing of the Danube River and the stopover in the settement named Baba (present-day Babadag, Romania) on his way. The way to Constantinople of another ambassador, Jędrzej Tarnowski, in 1560, crossed Kilia (now the town of Kiliia, Ukraine), Tulcza (present-day Tulcea, Romania) and Baba79. All these toponyms are shown on the map of Sarmatia, therefore the routes of travels on the beginning of the 16th century very likely were the same. Besides of the mentioned toponyms the lake Razelm (or Razim, without name on the map), Bialegrod (Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Ukraine) and Ren (Reni, Ukraine) near the mouth of the Danube River were marked.

For detailed examination of the toponyms of the map by Wapowski in Romania and Moldova it’s better to use the copy of this map. This is not the simplified map Polonia et Ungaria by Sebastian Münster, but the more detailed map by Georg von Reichersdorff80. With the assistance of Reichersdorff’s map the Romanian towns Galati (Galacz), Barlad (Berlach), Fălciu (Falcym) and Putna (Pudna) on the original map by Wapowski can be identified. The same applies to the toponym Lapuzna (Lăpuşna, Moldova). A mark without name between the Danube River and its tributary belongs to the present-day Romanian town Brăila. The map by Reichersdorff allowed to read one of the two toponyms between Baba and Varna: Chaliacra (the Kaliakra Cape).

The Slovak historian Lubomir Prikryl supposed that Bernard Wapowski used the manuscript map created by Stjepan Brodarić (István Brodarics), chancellor of the King of Hungary Louis II, as one of the sources of information for the map of Sarmatia. This map could have been received by Wapowski only in early 152781.

A special feature of the maps of Poland and Sarmatia by Wapowski is visible individualization of depictions of cities. The engraver of map of Sarmatia reflected his own knowledge about the typical architecture of a country, maybe even about the real look of particular towns and castles. That’s why the towns of Poland and Ukraine do not look like the towns of Moldova, Bulgaria or Turkey. There are no two identical pictures of the towns on this map. Depictions for various detailed pictures are typical for the nautical maps, i.e. portolani. Anoter typical feature of the portolan charts is marking of national emblems and flags on the appropriate territories. The map of Sarmatia contains pictures that more or less look like state emblems. Near the land names the emblems of the Principality of Moldavia and Podolia are placed. Pictures near the inscriptions LITVANIA and MOSKOVIA are not precise but reflexed the ideas of engraver about the state emblems of princedoms. The same can be said about the human face in the half-moon that marked the territories of the Ottoman Empire.

On the mappa mundi maps the textual information about particular places and events was often placed. Bernard Wapowski, following the mappa mundi, placed several texts about the important political events on his map. The inscription at the top of the map concerning the Battle of Orsha in 1514 has already been considered in the article. The text of the inscription between the Dniapro and Southern Buh Rivers near the picture of military camp, unfortunately, cannot be read precisely. According to Alexandrowicz, it refers to the "legendary, as related to the 11th century, successes of the Polish King Bolesław the Brave and Bolesław the Bold named Tiranus, (after all, both Boleslaws did not go so far) and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Vytautas; his tradition of military campaigns at the end of the 14th – early 15th centuries continued in the Black Sea steppes at least until the end of the 15th century 82".

Near the notation of the town of Varna the text is placed: "Hic Vladislaus Poloniae et Ungarie Rex contra Turcos apud Varnam und cum Juliano de Cesarinis Sanctii Angeli Cardinali fortissime pugnans occubuit". This inscription tells about the battle of Varna that took place in 1444 when the Ottoman army defeated the Hungarian-Polish and Wallachian armies. In this battle the King of Poland and Hungary Władywsław III was killed. The cardinal Giuliano Cesarini mentioned in the inscription had been sent by the Pope to Hungary to organize the crusade against the Ottoman Empire and also died in the battle. It is considered that the defeat of the combined military forces of Europe became one of the steps to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. On the map by Münster Poloniae et Ungariae, 1540, the inscription Campus Cassoius is placed which marked the Kosovo field that pointed out probably the place of battle in 1448 between a coalition of the Kingdom of Hungary and Wallachia against the Ottoman Empire. The similar or more detailed inscription should have been on the original map by Wapowski.

Finally, we shall make a suggestion. As mentioned above, the privilege to print two maps were given to Bernard Wapowski by Sigismund I in October 18, 1526. The first of these maps, map of Poland, was ready in the same 1526. Almost two subsequent years Wapowski busied himself with composing and printing the map of vast areas of Europe, from the Baltic Sea to the Turkish lands. This job required a lot of time and, possibly, money to gather information from multiple sources. The real client who financed creation of the map of Sarmatia was not the King of Poland but the Holy See, interested in receiving a real picture of Northern and Eastern Europe, and especially of the theater of war.

Footnotes:

1.For the biography of Bernard Wapowski see: Buczek 1966, 31, Szujski 1874, 9−18 (in the preface), Birkenmajer 1874, 156−163

2. Chowaniec 1955, 59–64. That refers to the maps Tabula Moderna Polonie, Ungarie, Boemie, Germanie, Russie, Lithuanie, prepared by Marco Beneventano for the 1507 Rome edition of the Ptolemy's Geography, and Tabula Moderna Sarmatia Evr/opeae/ sive Hungarie, Polonie, Russie, Prussie et Valachie, made by Martin Waldseemüller for the Geography by Ptolemy, printed in Strassburg in 1513. The prototype map by Bernard Wapowski has not survived to our time

3. Buczek 1966, 26. The map by Nicholas of Cusa created in 1456–1460 has survived in copies, the most famous of them, altered by Nicolaus Germanus, was printed in Eichstätt (Eystat) in 1491

4. The privilege was found and printed by E. Rastawiecki: Rastawiecki 1846, 10–13

5. Alexandrowicz 1989, 38

6. Conclusion about 1526 as the year of printing of the map is based on the line from the legend of the map: “6 Istula Crocam”. It suggests that the map was printed by “Florianus” in 1526 in Kraków on the Vistula River (Török 2007, 1819)

7. See editions of Atlas by Ortelius on www.orteliusmaps.com

8. Both Wallachias refers to the Principality of Wallachia and the Principality of Moldavia

9. Alexandrowicz 1989, 40

10. Alexandrowicz 1989, 48

11. Buczek noted that ‘prints of two sections of this map and fragments of the third lower section are shown reduced in fig. 8’ (Buczek 1966, 32) but the mentioned picture reproduced on Fig. 1 contains only two fragments

12. Török 2007, 1819

13. Buczek 1966, 33

14. Buczek 1966, 32–33

15. About the hypothesis of two editions of the map of Sarmatia see: Buczek 1966, 34; Alexandrowicz 1989, 40–42.

16. All modern reproductions of the map by Wapowski are printed after Monumenta Poloniae Cartographica, z.1, Kraków, 1939; tabl. II b, c.

17. Ulewicz 2006, 27–33

18. Regarding the toponym Russie in the names of maps by Beneventano, 1507, and Waldseemüller, 1513. Both maps are advanced versions of the map by Nicholas of Cusa (Eichstatt map, 1491, see footnote 3) where Rubea Russia is shown. Rubea Russia – the Red Rus’ in 16th century was the name of Halychyna, the historical region, which was at that time a part of the Kingdom of Poland

19. Ulewicz 2006, 52

20. Buczek 1966, 33−34

21. Samples of using the name Scythes concerning Tatars, see: Drozdov 2011, 21

22. The inscription will be concidered later in the text of the article

23. Кordt 1910, 11

24. Petrun’ 1924, 42

25. Buczek 1935, 10–12

26. Buczek 1966, 25–42

27. Alexandrowicz 1989, 38–70

28. Alexandrowicz 1977, 91−100

29. Buczek 1966, 34–35; Alexandrowicz 1989, 47–50

30. For example see the map in Buczek 1966, Fig. 9

31. For example see the map in Kordt 1910, 12

32. For example see the map in the annex to Alexandrowicz 1989. In Кordt 1899, 9–10, there is the map of Russia and Siberia (named “Russian Mercator”"), created, according to the author’s point of view, using not only the well-known map by Mercator, 1554, but the original, i.e. the map of Sarmatia by Bernard Wapowski

33. For example see the map in Коrdt 1910, 1

34. Vavrichin/Dashkevich/Kryshtalovich, 140–141; Buczek 1966, 35

35. For example see the map in Kordt 1910, 13

36. Buczek 1966, 35

37. It is worthy to note that in other parts of the map the particular attention is also given to the depictions of rivers.

38. Długosz 1867, 10, 20–21

39. Сitation from the edition of treatise: Litvin 1994, 98

40. The name of the city of Kremenchuk originated from the tatar word means "the little fortress"

41. Map of 1525 see in Fomenko 2007, 188. A version of this map was printed in 1554 see Коrdt 1899, 3

42. Evliīa Chelebi 1979, 701

43. Alexandrowicz 1989, 45

44. As in the map of Münster. Bagrow 2005, 120

45. Bagrow 2005, 122

46. Bronevski 1867, с. 134; Dashkevich 1990, 158

47. For example see the map on the website of the British Library: http://www.bl.uk/magnificentmaps/map2.html

48. In the Arabian and Persian diplomatic sources [Sbornik materialov 1941, 36–37, 121, 179]; in the Turkish diplomatical documents [Аbragamovich 1969, 76–96]

49. This map is presented in the Cosmography since 1544

50. See the map in Коrdt 1931; 39–41, Annex 1

51. Bagrow 2005, 96–103

52. Alexandrowicz 1989, 59

53. Alexandrowicz 1989, 57, 62

54. Zimin 1988, 188. For the precise dates of the embassy see PSRL 1859, 271–272.

55. Тext of the poem see in: J. Szujski 1874, 347–353

56. Buczek 1966, 32

57. Zvid 1999, 323

58. Тikhomirov 1952, 102

59. His name Simeon is a variant of the name Szymon. The name of his father was Alexander, the folk variant of this name is Olelko, that’s why the patronymic of the prince of Kyiv also has the variants Alexandrowicz or Olelkovich.

60. In the notification about the marriage in 1463 of Stephen the Great, Prince of Moldavia, with Evdokia, the sister of Simeon Olelkovich: Grekul 1976; 26, 63, 69, 106, 107, 118.

61. Goshkevich 1890

62. Zavitnevich 1891

63. Zvid 1999, 323

64. Bagrow 1964

65. Gordeev 2006

66. For example see the map in Buczek 1966, Fig. 3

67. Pallas 1999, 36

68. Evliīa Chelebi 1996, 149

69. The conclusion about the ligthouses is based on the white rectangles near their images looking like the rays of light. But Török 2007, 1818, considered them to be the white spaces to print the names of settlements

70. See footnote 2

71. Buczek 1966, 30

72. Strasbourg is marked on the map by Münster, 1540, therefore this town was marked on the original map by Wapowski

73. The name of the edition is Clavdii Ptolemei Viri Alexandrini ... Geographie Opus Novissima Traductione E Grecorum Archetypis Castigatissime Pressum. Maps from this edition are placed on the website of the library of University of Virginia (search.lib.virginia.edu)

74. Gordeev 2014, 19–76

75. The atlas of Piri Reis created almost at the same time, in 1525, shows only coastal settlements of the Anatolian peninsula. For example see: Book on navigation/Kitāb-i bahriye Published by: The Walters Art Museum, 2011

76. Gordeev 2014, 27, 37

77. Gordeev 2014, 315–316

78. Gordeev 2014, 26, 42, 60, 76

79. Podróźe 1860, 10, 36, 41

80. See the map in the book Moldaviae, quae olim Daciae pars, chorographia. http://nelucraciun.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/moldova-1595.jpg

81. In April, 1527, Stjepan Brodarić published in Cracow the treatise with description of the Hungarian-Turkish war and the battle of Mohács De conflictu Hungarorum cum Turcis a Mohacz verissima Historia ... Alexandrowicz 1989, 41–42

82. Alexandrowicz 1989, 46

Abragamovich, Z. 1969: ‘Staraīa turetskaīa karta Ukrainy s planom vzryva dneprovskikh porogov i ataki turetskogo flota na Kiev’ Vоstochnye istochniki po istorii narodov Īugо–Vostochnoī i Tsentral'noī Yevropy, 2, Moskva, 77–96.

Аbragamovich 1969, 76–96.

Alexandrowicz, St. 1977: ‘Stosunki z Turcja i Tatarszczyzna w kartografii staropolskiej XVI–XVII wieku’ in Polska–Niemcy–Europa, Poznan, 91−100.

Alexandrowicz, St. 1989: Rozwój kartografii Wielkiego ksiestwa litewskiego od XV do połowy XVIII wieku, Poznan.

Bagrow, L. 2005: Istoriīa russkoī kartografii, Моskva.

Bagrow, L. 1952: ‘A Russian Communication Map, ca 1685’ Imago mundi, 1952, 9, 99−101.

Bagrow, L. 1964: L. Bagrow’s addition to the article: Kohlin, H. ‘Some Remarks on Maps of the Crimea and the Sea of Azov’ Imago mundi, 1964, 15, 87−88.

Birkenmajer, L. A. 1900: ‘Marco Beneventano, Kopernik, Wapowski, a najstarsza karta geograficzna Polski’ Rozprawy Wydziału Matematyszno–Przyrodniczego Akademii Umiejętności, s. 3, tom 1, Kraków, 134−222.

Bronevskiī, М. 1867: Opisanie Kryma (Tartariae Descriptio) Martinа Bronevskogo in Zapiski Odesskogo Obschestva Istorii i Drevnosteī, 6, Odessa.

Buczek, K. 1935: Les débuts de la cartographie polonaise, de Długosz à Wapowski in Bulletin International de l’Academie Polonaise, 1-3, z. I–II, Kraków, 9−12.

Buczek, K. 1939: Monumenta Poloniae Cartographica, z. 1, Kraków, unpublished.

Buczek, K. 1966: The History of Polish Cartography from the 15th to the 18th century, WroclawWarszawaKraków.

Chowaniec, Cz. 1955: ‘The First Geographical Map of Bernard Wapowski’ Imago Mundi, 1955, 12, 59−64.

Dashkevych, Y. 1990: ‘Skhidne Podillīa na kartakh 16 st.’ Geоgrafichnyi faktor v istorychnomu protsesi, Kyiv, 155–158.

Długosz, J. 1867: Jana Długosza kanonika krakowskiego Dziejów polskich ksiąg dwanaście, I, Kraków.

Drozdov, Y. 2011: Tiurkskoyazychnyī period evropeīskoi istorii, Yaroslavl’.

Evliīa Chelebi, 1979: Kniga puteshestviīa (Izvlecheniīa iz sochineniīa turetskogo puteshestvennika 17 veka). Vypusk 2. Zemli Severnogo Kavkaza, Povolzh’īa i Podon’īa, Москва.

Evliīa Chelebi, 1996: Kniga puteshestviī Evlii Chelebi. Pokhody s tatarami i puteshestviīa po Krymu (1641–1667 гг.), Simferopol’.

Fomenko, I. 2007: Оbraz mira na starinnych portolanakh. Prichernomor’ye. Кonets 13 17 vv., Мoskva.

Gordeev, А. 2006: Kartografia Chernogo i Azovskogo moreī: retrospectiva. Part 1. Until 1500. Part 2. The period 1500–1600 years. Part 3. The period 1600–1700 years, Kyiv. Digital edition on CD.

Gordeev, А. 2014: Toponimiīa poberezhīa Chernogo i Azovskogo moreī na kartakh-portolanakh 16 17 vekov, Kyiv. Published on: Academia.edu.

Goshkevich, V. 1890: ‘Zamok kniazīa Simeona Olelkovicha i letopisnyī Gorodets pod Kievom’ Тtrudy Кievskoī Dukhovnoī Akademii, 2, Kyiv, 228–254.

Grekul, 1976. Slaviano-moldavskie letopisi XV−XVI st., Moskva.

Кеppen, P. 1837. Кrymskiī sbornik, Sankt-Peterburg.

Кordt, V. 1899: Мaterialy po istorii russkoī kartografii, 1, Кiev.

Кordt, V. 1910: Мaterialy po istorii russkoī kartografii, 2, Кiev.

Кordt, V. 1931: Мaterialy do istorii kartografii Ukrainy, Кyiv.

Litvin , M. 1994: О nravakh tatar, litovtsev i moskovitīan, Мoskva.

Pallas, P. 1999: Nabliudeniīa, sdelannye vo vremīa puteshestviīa po īuzhnym namestnichestvam Russkogo gosudarstva, reprint edition, Moskva.

Petrun’, F. 1924: ‘К voprosu ob istochnikakh Bolshogo Chertezha’ Zhurnal nauchno–issledovatelskikh kafedr v Оdesse, 1924, tom 1, № 7, Оdessa.

Podróźe 1860 = Podróźe i poselstwa polskie do Turcyi. Przygotowane do druku przez J. I. Kraszewskiego, Krakow.

PSRL, 1859 = Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopiseī, 8, Sankt-Peterburg.

Prikryl, L. 1977: Vyvoj mapoveho zobrazovania Slovenska, Bratislava.

Rastawiecki, E. 1846: Mappografia dawnej Polski, Warszawa.

Sbornik materialov, 1941: Sbornik materialov, otnosiaschikhsia k istorii Zolotoī Ordy, 2, Мoskva–Leningrad.

Szujski, J. 1874: Bernard Wapowski i jego kronika in Kroniki Bernarda Wapowskiego z Radochoniec kantora katedr. Krakowskiego częśċ ostatnia czasy podługoszowskie obejmująca (1480–1535), Scriptores rerum Polonicarum, II, Cracoviae.

Тikhomirov, М. 1952: ‘Spisok russkikh gorodov dalnikh i blizhnikh’ Istoricheskie zapiski, 40, Москва.

Török, Zsolt G. 2007: ‘Renaissance Cartography in East-Central Europe, ca. 1450–1650’ in The History of Cartography, 3, Chicago, 1806–1851.

Ulewicz, T. 2006: ‘Sarmacia. Studium z problematyki slowianskej XV i XVI w.’ in Sarmacia. Zagadnienie sarmatyzmu w kulturze i literaurze polskiej (problematyka ogólna i zarys historyczny), Biblioteka Tradycji, 46, Kraków.

Vavrychyn, М./ Dashkevych, Y./ Kryshtalovych, U. 2004: Ukraina na starodavnikh kartakh. Kinets 15 – persha polovyna 17 st., Kyiv.

Zavitnevich, V. 1891: ‘Zamok kniazīa Simeona Olelkovicha i letopisnyī Gorodets pod Kievom (Rezultat probnoī arkheologicheskoī raskopki)’ Chteniia v istoricheskom obschestve Nestora Letopistsa, book 5, part 2, Kiev, 134–141.

Zimin, А. 1988: Formirovanie boiarskoī aristokratii v Rossii vo vtoroī polovine 15 – pervoī treti 16 v., Moskva.

Zvid 1999 = Zvid pam'īatok istorii ta kultury, book 1, part 1, Kyiv.

| < Папярэдні | Наступны > |

|---|