Падобныя матэрыялы

- Габрыэль Буклен 1658 год. LITHUANIA

- Падробка рэдкай карты свету 1507 года Марціна Вальдзеемюлера

- Атлас Кленке (Klencke Atlas). Апошняе выданне карты ВКЛ 1613 года Вільяма Блаў

- Атлас Кленке (Klencke Atlas). Последнее издание карты ВКЛ 1613 года Вильяма Блау

- Насценная карта ВКЛ 1613 года з Веймарскай бібліятэкі

- Подделка карты мира 1507 года Мартина Вальдзеемюллера

- Grodno gravure 1568. Facsimile print

- Карта Великого Княжества Литовского образца 1613 года в библиотеках Польши, Украины и Литвы

- Историография первой настенной карты ВКЛ 1613 г. в печатных источниках

- Гістарыяграфія першай насценнай карты ВКЛ 1613 г. у друкаваных крыніцах

- Аб удакладненні датавання карты ВКЛ ўзору 1613 года

- Об уточнении датировки карты Великого Княжества Литовского образца 1613 года

- O doprecyzowaniu datowania mapy Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego z roku 1613

- THE ROLE OF CARTOGRAPHY IN FORMATION OF THE EASTERN EUROPEAN NATIONS: BELARUS CASE STUDY

On specifying the date of the map of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania of 1613

In this article, the author analyses the existing approaches to studying the states of the Amsterdam edition of the GDL map of 1613, and also suggests new ways of dating maps taken from the atlas.

The most common way to determine the publication in which the map was included is to identify the features of the text on the reverse side1. In the case of the GDL 1613 map, there is no text on the reverse in most cases. For this reason, the study is innovative, with some thesis requiring further clarification. However, because the map was originally published as a wall-map and later incorporated into atlases as modified, a number of features that allow for more accurate dating of the maps removed from the atlas can already be identified.

Until recently six states of the Amsterdam edition of MAGNI DVCATVS LITHVANIAE map of 1613 (the map is also called the Radziwill map, less commonly the Makovsky map) were described in literature. Four of them belong to the atlas editions and were described by Frederik Wieder back in 19292. There are two other wall maps, different from each other in a number of features, which are often referred to by their location – “Uppsala” and “Weimar”.

Uppsala and Weimar wall maps of GDL of 1613

In 1913, Ludwik Antoni Birkenmajer3 discovered and published a small note about what he thought to be a copy of the first wall-map of the GDL of 1613, that had been found in the University Library of Uppsala, Sweden. The description of the find was very sparse and took up a single page in a university collection. The note did not include the most important thing, a photograph of the map. For the first time, a photograph of the Uppsala map was published only in 1964 by the Lithuanian scientist Povilas Reklaitis4; before that, maps from the atlases were used in research (published since 1631). This was noted by the Polish scientist Stanislaw Alexandrowicz5.

Because the map was glued to the fabric, the elasticity of the paper was poor, small fragments were lost, and there were many paper breaks. Wooden stretch strips were attached to the map at the top and bottom. The map was restored several times. The last time was in May 2016: cloth and wooden strips were removed, and the map was cleaned of dirt and glued to the paper base.

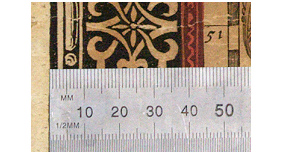

In his note, Birkenmajer inaccurately indicated the size of the map (107cm x 82cm without a frame). According to Birkenmajer's measurements, the width of the decorative frame was 5 cm, but it did not exceed 4.4 cm. On closer examination, it can be seen that the printing plate for the frame was made of wood (Fig. 1). It is not indicated that the map is significantly deformed horizontally and vertically: this is primarily due to manual gluing of separate fragments. After the 2016 restoration, the map was smoothed out and the size given by Birkenmajer became even more different.

THE SIZE OF THE UPPSALA MAP AFTER THE 2016 RESTORATION:

Width (cm)

• Upper edge: 105.5 (without frame); 116 (total)

• Lower edge: 103.5 (without frame); 114.5 (total)

Height (cm)

• Left edge: 74.5 (without frame, without text); 82.8 (without frame, with text); 123.5 (total)

• On the right edge: 73.5 (without frame, without text); 81.5 (without frame, with text); 122 (general).

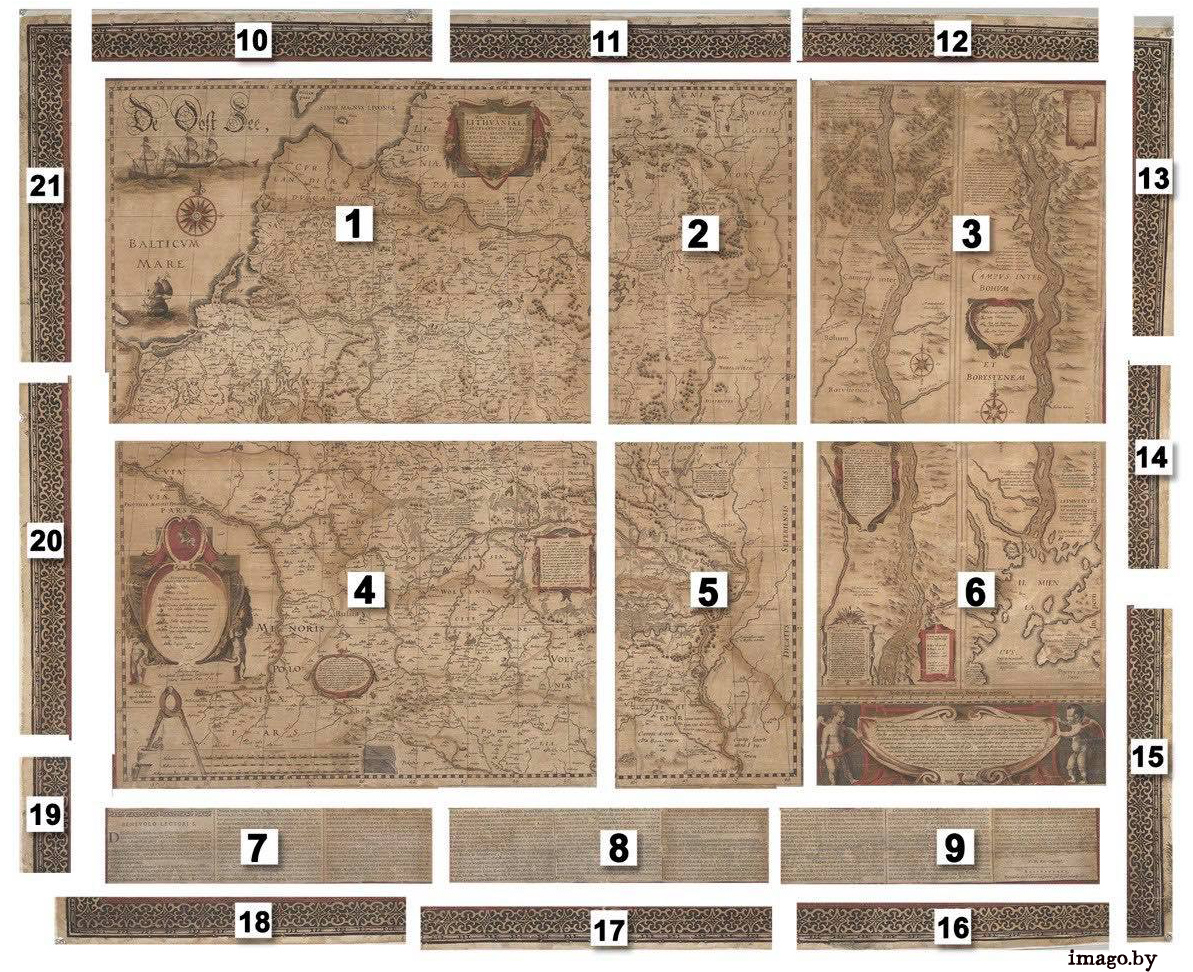

Algirdas Gliožaitis, in his book published in 20176, addressed the subject of components of the map. He singled out 19 different glued fragments of the map, but he made a mistake by combining two elements of the decorative frame into one large (10 and 11, 17 and 18). This is probably due to the study of the map before the last restoration; after the 2016 restoration, it was easier to look at the constituent parts of the frame and see 12 fragments rather than 10, as previously stated by Gliožaitis. In total, 21 components of the entire map have been identified (Fig. 2).

Before Gunter Schilder found a second wall-map in the attic of the castle in Weimar in 1984, literature indicated that this copy was the only surviving wall-map from 1613. The author of the finding later determined that the Uppsala map had been printed from 6 plates7, i.e., after dividing 4 copper plates into 6 (in 1631, the two right plates were cut to separate the Dniapro (Dnipro, Dnieper) from the main map, and the decorative strips along the edge of the map were also separated from the printed plates). The Weimar map was printed from four plates, so the Uppsala map was printed after 1631 and is inferior in age to the Weimar map.

Atlas editions and their state

Between 1631 and 1649, some 20 editions of Blaeu8 atlases were published, including the Radziwill Map of 1613. As indicated, only 4 major atlases were identified in the bibliographic handbooks. The author relies on the structure developed at Gunter Schilder's Monumenta cartografica Neerlandica9 but makes a few significant refinements.

State 29.1 – wall-maps described above.

State 29.2 (KAN 2:02110) - first Latin edition, 1631.

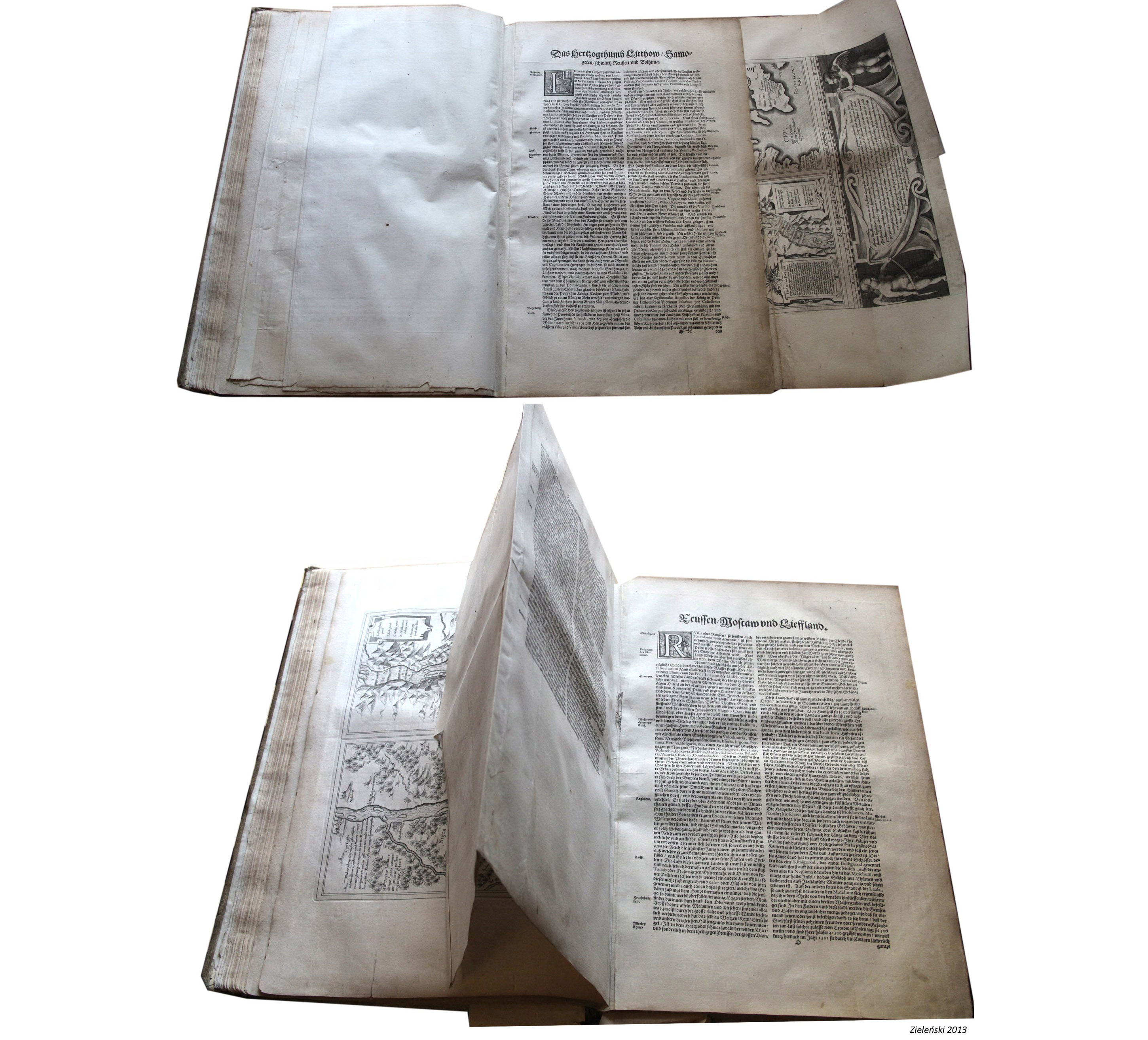

G. Schilder provides the following information – «This state lacks the text along the low edge. In this form the map is included in the first version of Blaeu's 1631 Appendix. In this edition of the atlas, the four sheets... have a printed text in Latin on the back with the signatures N2, N2, N4, and N5.». It's important to clarify this phrase. The text on the back of the map is NOT the text on the front of the wall-map copy (better known as Makovsky's text). Makovsky's text was attached on additional sheets, but without the signature of “T.M. Pol. Georgraph.”.

The text of the description of Lithuania is 8 pages long and in abbreviated form reprinted from the book Respublica sive status Regni Poloniae, Lituaniae, Prussiae, Livoniae etc. diversorum autorum, published in 1627 by the Elzevier publishing house in Leiden. In turn, the basis for this book text was the Chronicle of European Sarmatia by Alessandro Guagnini, published in 1578 in Krakow in Latin.

In the first edition of Appendix the map was printed on 4 separate sheets and placed in an atlas.

State 29.3 – second Latin edition 1631 (KAN 2:022).

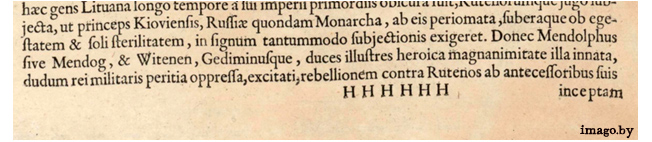

Shilder indicates the following map changes: «Blaeu changed the arrangement of the map sheets; he separated the map of the river Dnjepr from the map of Lithuania. The original decorative border surrounding the entire map has disappeared. The lower left sheet of Lithuania has a printed text on back with the signature 'HHHHHH'; the remaining parts of the text were printed on separate sheets and added as 'additional sheets'. The same was done to the map of the Dnjepr: the back of the upper part of the map bears a text with the signature 'IIIIII'; the lower part has been added as an 'additional sheet'.

The maps arranged in this way appear in the second version of the 1631 Appendix.»

Originally the map of GDL 1613 was printed on 4 separate sheets, the use of such a non-standard map in the atlas was inconvenient. Blau does not produce new printed forms of standard format (it happened only in 1649), but looks for a way to reduce the wall map GDL (separates the Dniapro from the main map, removes the decorative strip).

In the second edition of Appendix the map is presented in glued form and separately from the map of the Dniapro.

It became impossible to place text on folded maps, which led to the redistribution of text. Text was printed on the back of the bottom left-hand page (the beginning of a large text about Lithuania), signature “HHHHHH” was added to the bottom (binder mark); the rest of the text was printed on separate sheets and added as "additional sheets", but also with an added signature – “HHHHHH”.

On the reverse side of the Dniapro in the upper part of it there is the text of Makovsky without the signature “T.M. Pol. Georgraph.” The text occupies 2/3 of the map (since the map was scanned horizontally, the text is printed perpendicular to the river flow). A distinctive feature of the Dniapro from this edition is the signature at the bottom of the text “IIIIII”, the second part of the text was added as an “additional sheet”.

State 29.4 – German edition 1634 (KAN 2:131).

According to Schilder: «In 1634 Blaue again rearranged the map sheets. The mounted map of Lithuania is included in the German edition of the 1634 Atlas without text on the back; the map of the Dnjepr is found in the 1634 Atlas in the same form as in the second version of Blaeu's 1631 Appendix (no. 29.3); the text has the printed signature 'O', which has been changed in manuscript to 'N'.»

In 1634, Blaue published the German edition of the atlas. In this edition, the large text was already completely missing from the map of Lithuania, it was placed on separate sheets and printed in German. The text on the map of the Dniapro was printed in the same way as in the previous edition, but with the signature "O" or “N”. In the German edition of 1635, only the signature “N” appears on the map of the Dniapro.

State 29.5 – all editions from 1635 to 1649.

Schilder classifies all other maps as this state: «In the atlas editions of 1635 and in subsequent in 3, 4, and 6 volumes, both maps were printed separately and included in the atlas without text on the back. In the Atlas maior in its most complete form in various languages, both maps were replaced by more modern ones.»

This most massive segment has no other Radziwill map states, and there are no text or signatures on the back. Moreover, it is not clear what is the difference between states 29.4 and 29.5 for an GDL map. We are talking about a total of 18 atlases11 with GDL maps without any differences detected.

The map of the Dniapro was further printed as a separate map dated 1649 (and also in Atlas Major 1667), in some cases the map lacks text and a signature, in some cases there is a signature12.

State and defects of printing plates (damage on the copperplate)

Two main directions were chosen for detailed classification of maps, which help to date works on paper in detail: description of plate state and defects of the printed plate.

One of the most famous ways to date maps is the features of text on the back. For maps published in atlases, there are special guides from which you can determine the distinctive features of different editions of the same map. Thus Marcel van den Brock in his book «ORTELIUS ATLAS MAPS An illustrated Guide», analyzing the maps of Abraham Ortelius' atlas, was able to identify several states of printed plates for almost every map. Brock showed by examples that the printed plates could not only be restored (Nb: and this was a widely accepted practice), but also corrected in the process of use: changes were made in the names of cities, the contours of seas were expanded, names of rivers were changed, etc. For the map of Europe (years of publication: 1570-1587) Marcel van den Brock was not only able to describe all the possible editions of the map, based on texts on the back, but also highlighted 3 states of the plates. In some cases, even mentioning such trifles as increasing the hatching area from 2 to 4 mm. All this indicates that in a relatively short period of time (17 years), the printed form could have changed considerably.

As mentioned above, from the text on the back of the Radziwill map from the whole array of publications can be identified only the first and second Latin edition. All other publications were printed without text or signature on the reverse.

The author of this article has worked out a hypothesis that in the period from 1631 to 1649 the original printed plates had to be modified, if not fundamentally (serious changes - addition of cities, change of the outline of rivers or coastline, etc.), then there must have been defects arising in the course of existence (scratches, reduction of lines of the original markup, etc.), which will allow to separate the array of prints to "earlier" or "later" editions.

More than three dozen maps of GDL of 1613, both in a set of atlases and taken from them, were examined. The work is complicated by the fact that Blaeu atlases are scattered all over the world, are in public and private collections, images quality and completeness of information are limited for various reasons.

The literature of the history of engraving indicates that up to 1000 prints could have been printed from one copper plate. In the author's opinion, this figure is applicable only to artistic works. Thus, according to van den Broecke, which he cited as an example of Ortelius' atlases, not only small defects appeared on the plates, but even cracks (in circulation about 1500 prints, in some cases for the first time appeared on 3800 prints) - and this did not lead to a change of printing plates. They continued to be used, and the total number of impressions from one plate could reach 5000-7000.

Unity of the printing plate (copperplate)

Although many sources indicate that the printing plate (of the 4 parts, later divided into 6) was the same throughout the GDL map publication of 1613, the author considered it important to check this. It was necessary to find out the smallest details that appeared at the stage of plate making and were present on all subsequent prints (scratches, thin lines, errors in the drawing).

To confirm the unity of plate hypothesis, 4 places with the smallest details were chosen (Fig. 7). It is safe to say that one printing plate was used.

Initial marking lines

Using the analysis of the original marking lines, you can determine, with some approximation, which sheets were printed earlier and which were printed later. Together with the marking lines, you can find prints of random lines, inaccuracies, corrections and even small defects of the board itself on the early sheets, which gradually disappear and are not visible on later prints.

When lines of the original markings exist, they disappear primarily due to their minimum depth. On the 1613 map, the lines of the original marking are clearly visible on text cartouches as well as on the wind rose. In the study, the author focused on the wind rose, because a large number of marking lines were used to draw it.

As shown in Figure 8, in the Weimar and 1631 editions, the marking lines are very clearly visible, including the lines within the smallest circle. From 1635 onwards, lines become less visible. The 1638 editions have a partial presence. In 1640 editions, markup lines are practically not found, a certain sequence of disappearing lines can not be identified. These observations only indicate the gradual disappearance of shallow lines in the process of using printed plates, but they do not allow for a separate map to be dated with sufficient accuracy.

Plates’ state

In the second stage, the author focused on conscious (deliberate) publishing changes in plate. The analysis of 28 prints revealed two new states, not previously described:

State A29.6 - since 1643.

The Ducatus Severiensis Pars inscription shows a dot after the word Severiensis:

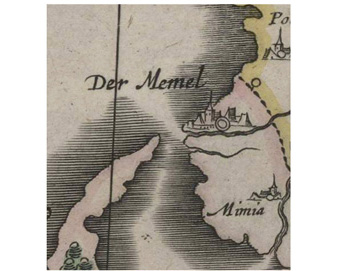

State A29.7 – c 1645 and later.

The city name of Der Memel is engraved. Note the presence of a German prefix on a mostly Latin map:

Defects of plates

It is conscious publishing changes in the printed plate that can be classified as states. In theory, it is not accepted to categorize random defects on printed plates as separate states. But in a situation when it is difficult to determine whether a map belongs to this or that atlas, the author allowed himself to introduce additional gradation of maps on the identified stable defects.

There are two types of defects on the plate: those occurring in the course of existence (scratches, damages), which were absent on older prints and appear on older "newer" prints, as well as corrections, which disappear from the "newer" prints but are present on older ones (as a result of printing and possibly restoration of forms). Defects related to the quality of the print itself have been eliminated from the entire data set.

Additional printing plate states corresponding to the detected defects:

Defect A29.d1 – from 1640 to the last edition.

The defect appears as a point east of Mulhausen and west of the Passaria River. And a large spot northwest of the town of Neidenborg.

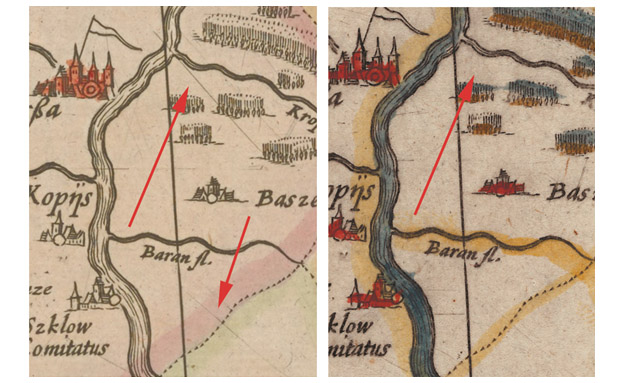

Defect A29.d2 - from 1643.

A significant scratch disappears in the Orsha area. It's been there since 1635. Previously it passed through the confluence of rivers in the direction from north-west to south-east.

This approach requires further practical improvement through the study of Blaeu's atlases. A number of factors make the work difficult, such as the inclusion of old stocks in subsequent atlases; dating atlases sometimes presents problems: Blaeu Publish House has used outdated title pages with handwritten dates (handwritten corrections are even present on maps) and a number of others.

At the same time, we can already make some clarifications now. Prior to this article, we could only claim that the Uppsala map could have been printed at Blaeu Printing House as a special wall version of the map in the period that begins after the division of the printed plates into 6 pieces (i.e., not before the second edition of the 1631 Atlas) and ends in 1672, when a fire destroyed a printing house in Amsterdam. However at the analysis of the printed plate it is visible, that it has distinctive features which allow to define date of the press in the interval 1635-1638. And according to lines of a marking, it more corresponds 1638, rather than 1635.

References:

1. Marcel van den Broecke. ORTELIUS ATLAS MAPS An illustrated Guide, 2011 (second revised edition); Cornelis Koeman, Peter van der Krogt. Atlantes neerlandici. V.2 The folio atlases published by Willem Jansz. Blaeu and Joan Blaeu., 2000

2. Frederik Casparus Wieder. Monumenta Cartografica. Reproductions of unique and rare maps, plans and views in the actual size of the originals; accompanied by cartographical monographs. Vol. III., 1929. P.69

3. Ludwik Birkenmajer. Wiadomośc o mapie geograficznej Litwy Tomasza Makowskiego (z r. 1613) uważanej za zaginioną. Sprawozdania Akademii Umijętności. T. 18, №4., 1913. P.24-25

4. Povilas Reklaitis. Lietuvos senoji Kartografija / P. Reklaitis // Tautos praetis, t. II, kn. 1(5)., 1964. P.374

5. Stanisław Alexandrowicz. Mapa Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego Tomasza Makowskiego z 1613 r. tzw. "radziwiłłowska", jako źródło do dziejów Litwy i Białorusi, 1965. P.38

6. Algirdas Antanas Gliožaitis. Lietuvos didžiosios kunigaikštystės žemėlapis ir jo variantai, 2017. P.144

7. Schilder, G. Monumenta cartografica Neerlandica. T. IX. (3 Vols): Hessel Gerritsz (1580/81 - 1632), 2013. P.216

8. Cornelis Koeman, Peter van der Krogt. Atlantes neerlandici. V.2 The folio atlases published by Willem Jansz. Blaeu and Joan Blaeu., 2000. P.501-502. In the period from 1631 to 1649 the main body of atlas maps of GDL 1613 was published. In 1660 there was a single edition of GDL maps without the Dniapro in Klenke Atlas. Also around 1670 there was a counterfeited undated German edition of the atlas.

9. Schilder, G. Monumenta cartografica Neerlandica. T. VI., 1990. P.75-77

10. The map states of 1613 can be adjusted to match Blaeu atlases (numbering of atlases by C.Koeman, P. van der Krogt. Atlantes neerlandici. V.2, 2000)

11. C.Koeman, P. van der Krogt. Atlantes neerlandici. V.2, 2000. P.502

12. Ibid, C.503

| < Папярэдні |

|---|